The modern image of an angel in the popular mind is a young man in a white tunic and a thin golden nimbus with huge bird's wings. However, artists did not immediately begin to draw the heavenly messengers just like that. Although they are mentioned 273 times in the Bible, all the descriptions of seraphim and cherubim are fragmentary and do not contain detailed instructions on how they should be depicted. The Greek "angelos" - "messenger" - indicates rather the function of these beings, who are more often referred to simply as "men".

The absence of detailed portrait characteristics gave rise to many interpretations of the image. This is how balding and wingless male angels, effeminate or sexless winged creatures, zoomorphic four-headed, four-legged and four-winged chimeras, and non-anthropomorphic wheels with eyes appeared.

Beard and baldness: the male angel

In one of the Psalms, angels are described as beings composed of fire and wind. In Daniel's vision these creatures are able to move through the air: "Gabriel the man ... came quickly, and touched me about the time of the evening sacrifice" (Dan. 9:21). Matthew adds that the angel "looked like lightning" and his clothing was "white as snow" (Matthew 28:3). This is basically the most detailed description of the appearance of the heavenly messengers.

In the early Christian frescoes and marble sarcophagi, angels, for lack of details about their appearance, looked exactly like humans. The first such images appeared in the second half of the third century on the walls of the Roman catacombs. Angels cannot be distinguished from ordinary human beings if one does not know the subject. For example, in the dungeon of Priscilla Gabriel, bringing good tidings to the Virgin Mary, looks like a man with a short haircut and a white dress. The three angels in the scene of Abraham's hospitality in the catacombs of the Via Latina are ordinary young men, not distinguished in any way from the other characters in the frescoes.

All the same male characters we see in the biblical episodes depicted on the sarcophagi. Sometimes some of them are even bearded or bald, like the angel on the 4th century tomb from the Pio Cristiano Museum in the Vatican, who stops the hand of Abraham sacrificing his son to God. Apparently, so the artists wanted to show that the messengers of heaven could appear on earth and talk to people, and therefore they should look anthropomorphic, so that man is not afraid of them.

Dogma

Dogma

- USA, 1999.

- Fantasy, drama, comedy, adventure.

- Duration: 123 minutes.

- IMDb: 7.3.

Still from the film "Dogma".

Two fallen angels are stuck in backwater Wisconsin. But they have a chance to return to heaven. By going through the archway of the church, they will be cleansed of their sins and able to go to heaven. But then God would have made a mistake, and that is unacceptable. The world cannot bear such a logical breakdown, the end of the world might come.

Kevin Smith's daring and driving comedy was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1999 and quickly achieved cult status. The American director openly mocks religious dogmas and symbols of Christianity, and it turns out very funny. The roles of fallen angels are played by longtime friends Matt Damon and Ben Affleck.

Flight and androgyny: the winged angel.

By the end of the fourth century, it had become important for artists to distinguish angels from humans, and hence the need for specific visual markers. Since the Bible only mentioned in passing that heavenly messengers could fly, theologians began to pay close attention to this detail as early as the second or third centuries.

Tertullian wrote that both angels and demons are winged. John Chrysostom in the late fourth century argued that the wings allow God's messengers to descend quickly from heaven to help people, although they do not relate to their immaterial nature. The appearance of the angels was identified with the appearance of the Holy Spirit, whom the Lord also repeatedly sent as a winged herald to earth.

At some point these two images merged in the view of theologians to such an extent that the scene of the heavenly intercession of the Archangel Michael for the three young men in the furnace of fire depicts a dove rather than an anthropomorphic being. In their appearance, the angels became more and more similar to God and "distant" from man.

But over time the ranks of the worshippers of the heavenly messengers expanded, and the theologian Novatian wrote that Christ Himself belonged to the latter.

At the Council of Laodicea, held in the middle of the fourth century, it was decided to ban the cult of angels as idolatry and to punish Novatian for his heresy.

Now artists were faced with a difficult task - not only to identify the messengers of heaven among men, but also to show their difference from God, who wore a halo and surrounded by the glow-mandorla, and Christ, incarnated on earth in the form of a man. The solution, however, was quickly found by giving the heavenly messengers wings, thereby emphasizing their function as well as their position between God and men, between heaven and earth. In this way it was possible both to fulfill the prescriptions of the Council of Laodicea and to reveal the syncretic nature of these beings, almost never described in the Bible.

In addition, there were suitable iconographic prototypes in the Roman pre-Christian tradition, such as the image of the peplum-clad, winged goddess of victory Nika. She regularly appeared on the reverse of gold coins between portraits of Roman or early Byzantine co-Emperors with crowns and halos - for example, between Valens and Valentinian I. These images were the basis for the first Christian depictions of saints and later of the Trinity.

For example, Christ crowns the apostles Peter and Paul on one gold bottom. This scene is exactly copied from the coin, where the place of the Savior is the goddess Nika. The image of the royal trinity with the central winged character, in turn, could come to Roman money from ancient Egyptian art, where in the same manner in the II century BC on stone gems depicted Bait (one of the incarnations of Horus), Hathor (patroness of motherhood) and Akori (pharaoh goddess of power).

Gradually the image of winged creatures, copied from the goddess Nika and genetically going back to the iconography of Roman coins and ancient Egyptian gems, became standard for Christian culture.

In the fifth century one still encounters unusual works of art in which old and new canons are mixed. For example, on an Italian ivory panel kept in the British Museum in London, we see a heavenly messenger in a toga with wings, a beard and mustache, blessing the baptism of Jesus. In the future, however, angels will never look so manly again.

Perhaps, among other things, this is due to the fact that the viewers of the IV-V centuries understood that such an image is syncretic in nature and dates back to both descriptions of biblical "men" and the image of a pagan goddess. The heavenly messengers now had a kind of gender neutrality, supported by Scripture (Luke 20:27-36) and the authority of theologians: Jerome of Stridon, for example, argued that God and angels could not have gender.

The Wheel and the Beast-Eyed Monster: The Angel Chimera

Almost the only place in the Bible where angels are described in some detail is the vision of Ezekiel. At first the prophet does not specify what kind of creatures he saw, and speaks of strange creatures with four heads - a calf, a man, an eagle and a lion:

"...Their appearance was like that of a man; and each one had four faces, and each one had four wings; and their feet were straight, and their feet were like the foot of a calf, and glittered like shining copper. And the hands of men were under their wings, on their four sides; and their faces and their wings were all four of them; their wings were touching one to the other; in the course of their procession they turned not round about, but walked each in the direction of his face. The likeness of their faces is the face of a man and the face of a lion on the right side of all four of them; and on the left side the face of a calf on all four of them, and the face of an eagle on all four of them.

When they walked, they walked on their four sides; they did not turn around during the procession. And their rims were high and fearful of them; the rims of the four around them were full of eyes" (Ezekiel 1:5-18).

And only in chapter X will it be said that this is one of the angelic ranks, the cherubim:

"And the Cherubim lifted up their wings, and rose up in my eyes from the earth; when they departed, the wheels were also under them; and they stood at the entrance of the east gate of the house of the Lord, and the glory of the God of Israel above them. These were the same animals that I had seen at the foot of the God of Israel at the river Hovar. And I knew that they were Cherubim" (Ezekiel 10:19-20).

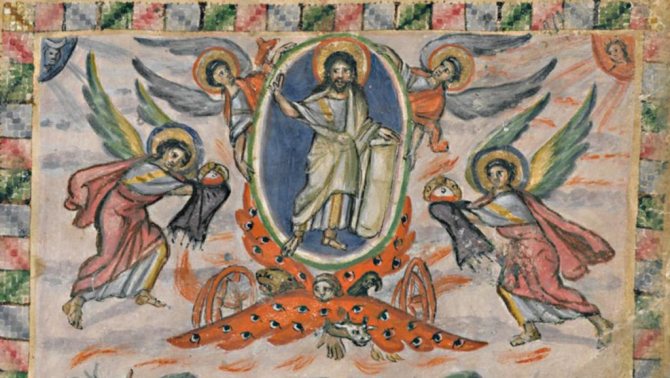

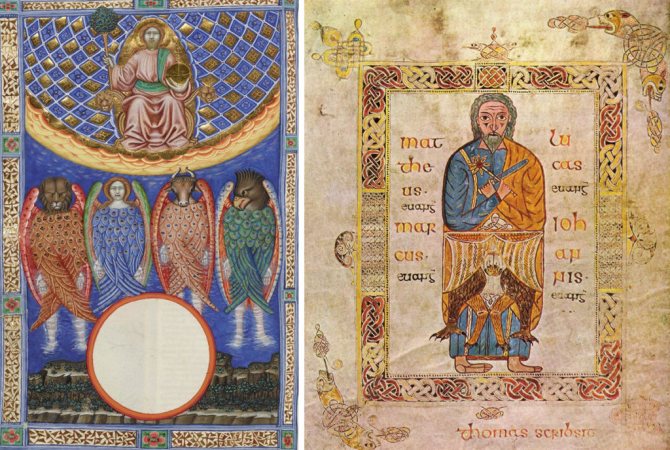

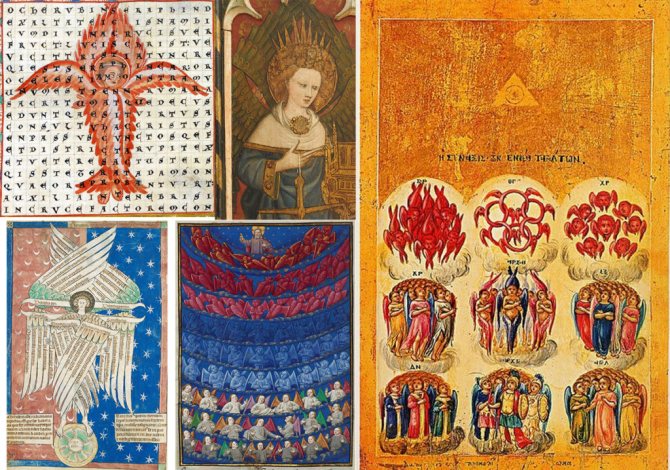

Already in the early Middle Ages, church artists tried to depict the angels described by the prophet as closely as possible to the text. The quadrupedal beings came to be called tetramorphs - and were considered a special kind of cherubim that surrounded the Lord's throne. Because Ezekiel's "verbal portrait" was extremely confusing and difficult to visualize, Christian craftsmen over the centuries have drawn them in many different ways.

For this reason, the pages of medieval Bibles often contain images of creatures with the heads of man, bull, lion, and eagle. In their bodies, their legs are juxtaposed with paws or wheels, dotted with eyes, and their arms with wings.

At times we do not see a single "organism," but rather wings fitted together, to which - with more or less anatomical conviction - are attached four heads, as well as wheels that turn the tetramorph into the cart of God. This is how the angel is depicted in the earliest surviving image of its kind from the Syriac Gospel of Rabulah, 586.

The angel (in the usual sense of the word), however, was more commonly depicted with the other three heads attached to it. Sometimes, in an effort to emphasize the special nature of the tetramorph and perhaps diminish its monstrousness, masters tried to disguise the three animal mouths by drawing them, for example, as part of the cherub's hair.

However, not all tetramorphs are based on the human figure. There are many depictions where they appear in an animal guise - as bull-like beasts with four different heads, wings and arms growing directly out of their bodies, or as a winged hybrid with four legs and four heads, resembling not a living creature, but rather an object of temple utensils.

Since the twelfth century, such divine monsters have sometimes been contrasted with diabolical monsters, such as the beast with seven heads and ten horns, which serves as the throne for the harlot of Babylon in the Revelation of John the Evangelist. Thus appears the allegorical representation of the Church riding the tetramorph, a hybrid of man, lion, calf, and eagle. In this context, it symbolizes the testimonies of the four Gospels, on which the Christian teaching is based.

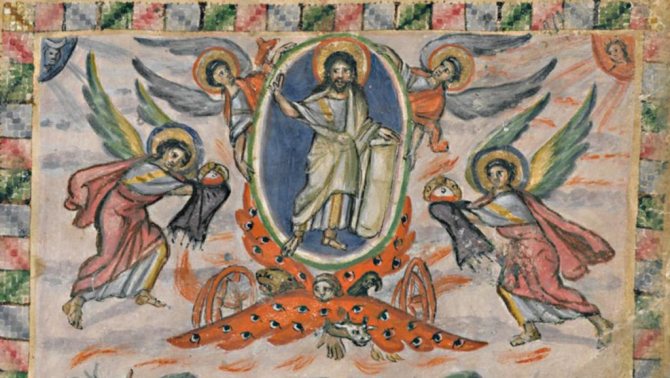

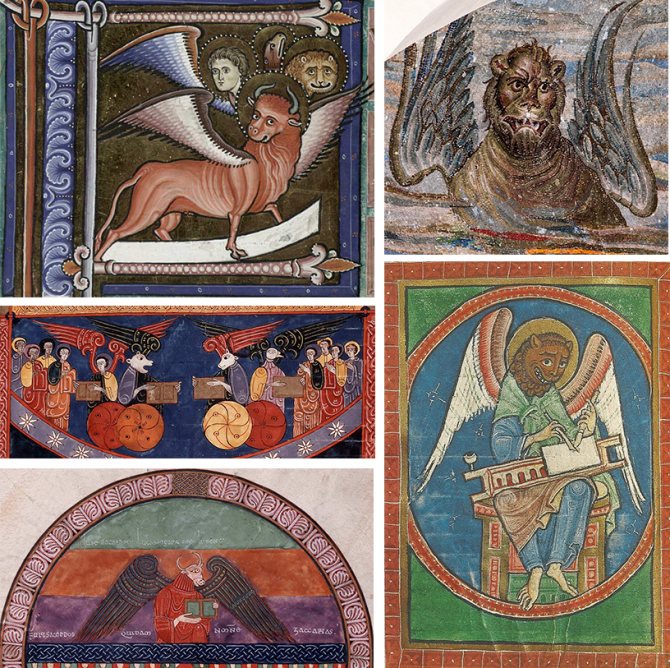

Along with images of chimerical creatures, there were also illustrations with four separate angel-like beasts. In the New Testament Revelation of John the Evangelist, the tetramorphs from Ezekiel's vision are reinterpreted and "broken up" into individual "animals."

"...in the midst of the throne and around the throne four animals, filled with eyes in front and behind. And the first animal was like a lion, and the second animal was like a calf, and the third animal had a face like a man, and the fourth animal was like an eagle flying. And each of the four animals had six wings around, and within they were full of eyes; and they have no rest day or night, crying out, 'Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty, who was and is and is to come'" (Rev. 4:6-9).

In Christian tradition, these images have been interpreted as symbols of the four evangelists. According to the most common version, the angel stood for Matthew, the lion for Mark, the bull for Luke, and the eagle for John. At the same time, in some depictions the four beings were "merged" into a tetramorph to emphasize the idea of the unity of the apostolic witnesses to Christ.

For example, in the generalized image of the Evangelists we see zoomorphic motifs: the bearded man has a pair of human legs, wearing sandals, but in front of him, as if from behind a screen, hang eagles' and lions' paws and bull's hooves.

In one body the heterogeneous elements are fused, which makes it resemble the tetramorph from Ezekiel's vision.

In other images, widespread since the beginning of the fifth century, the symbols of the evangelists are not anthropomorphic at all. For example, on the mosaic on the apse of the Roman basilica of Santa Pudentiana we see Mark the lion in human clothing with wings behind his back. In the Middle Ages, they would appear in both zoomorphic and anthropomorphic symbols of evangelists, demonstrating their angelic essence. And in Spanish manuscripts of the Apocalypse with an interpretation by Beatus of Liebant (8th century) the biographers of Christ were sometimes also depicted with wheels instead of feet.

Vrubel's Demon

A cycle of illustrations to Lermontov's poem "The Demon" was created by Mikhail Vrubel in the late 19th century - in 1890. Separately, Vrubel created his famous painting "The Demon Sitting" - now kept in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

"The demon is not so much an evil spirit as a suffering and mournful one, but at the same time a spirit of power and majesty..." .

He sits with his arms folded, surrounded by unseen flowers, staring with huge eyes either into the distance or into himself. He looks sad, solemn, alluring, and, needless to say, it is interesting to sit and chat with him.

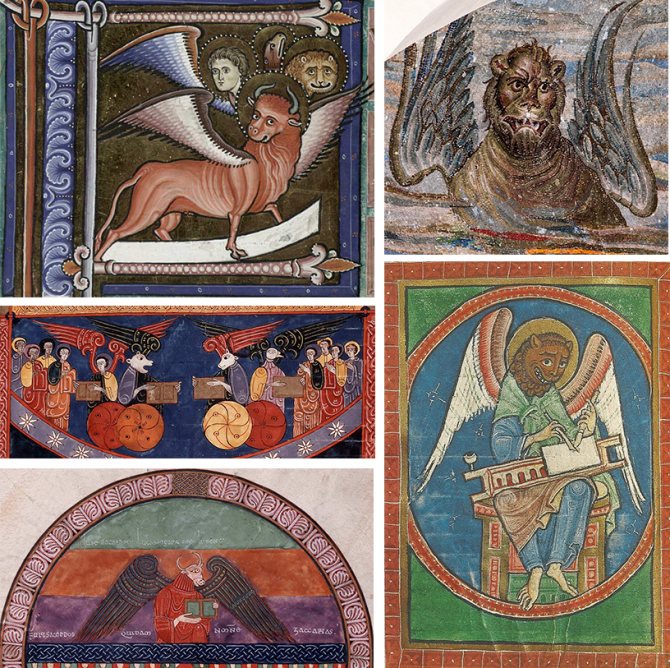

Living fire and countenance with wings: the angelic ranks

By systematizing Ezekiel's visions and other biblical evidence, the fifth- and sixth-century theologian Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite created a classification of the nine angelic ranks. He placed the "cherubim" contemplating the throne of the Most High second after the fiery "seraphim", who represented the flame of divine love. Then came the throne-bearers of the Lord, the "thrones.

Next came the "lords" who were constantly exalted in their greatness, the mighty and godlike "powers" who wielded the spiritual energy of "authority", the "superiors" who were responsible for the sacred order, the "archangels" who governed the lower ranks, and the "angels" who conveyed divine revelations to men.

Under the influence of the theology of the Areopagite and other theologians, artists began to paint the messengers of heaven in a differentiated way, given their rank. Seraphim were depicted with four or six wings of fire, or sometimes illustrators simply painted their plumage red instead of flames, in which case these characters resembled exotic birds.

Cherubs were represented in the same way, only without fire, and sometimes their legs and arms and sometimes their face were completely hidden by giant wings. Thrones could be painted as winged wheels studded with eyes, or as anthropomorphic beings with a huge throne in their hand.

The other ranks were usually depicted as similar to the previous ones. Visual hierarchies emerged: angelic groups were tried to be shown as different beings seated successively in the nine heavens (sometimes a tenth "regiment" was also drawn - the place of the absent Lucifer and his minions). Such depictions existed not only in the West, but also in Orthodox icons: on one of them we see all nine angelic ranks depicted in completely different ways.

Meet Joe Black

Meet Joe Black

- 1998, USA.

- Fantasy, melodrama, drama.

- Length: 178 minutes.

- IMDb: 7.2.

The Angel of Death decides to take a vacation and spend it among people. To do so, he inhabits the body of a handsome young man named Joe Black. The guy is in love with the daughter of a 65-year-old newspaper magnate. The elderly man has to help Death settle into the world of the living, and then he goes with her to the other world.

The script is based on Alberto Casella's play Death Takes a Day Off. The magic of this picture led to a short-lived but tumultuous romance between Brad Pitt and Claire Forlani (the central roles). The film can be called one of the best romantic films of the last 30 years.

Watch on iTunes → Watch on Google Play →

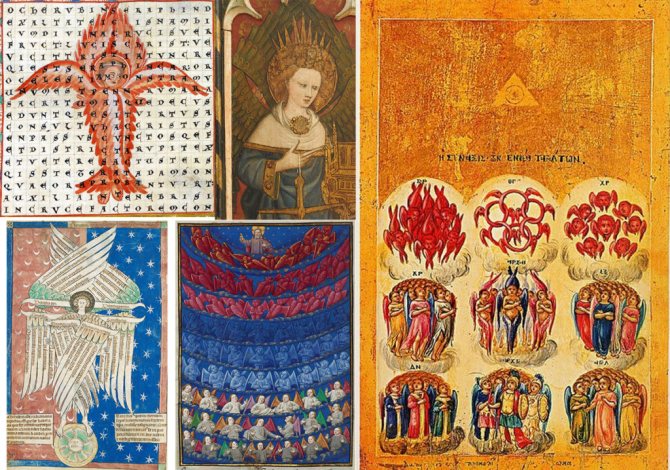

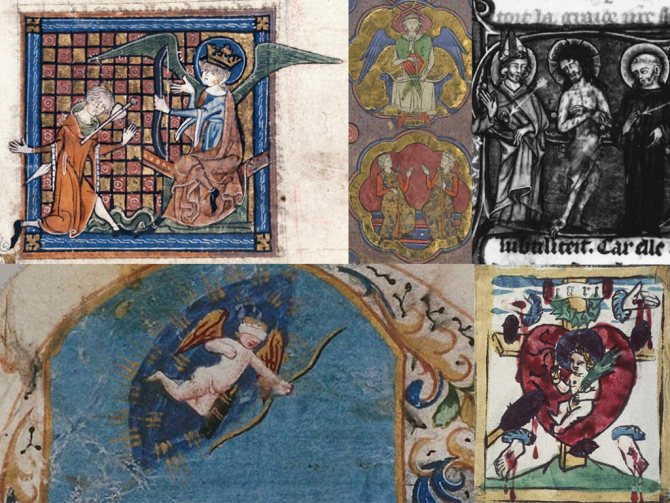

Eros, putti and arquebusiers: the sweet angel

The ancient image of Eros had a huge influence on early Christian art. The little winged creature with the bow became the "model" for drawings of the soul soaring into the sky.

In the Middle Ages, the iconography of the God of Love, a distant descendant of the ancient Eros, began to converge with the image of Christ thanks to the spread of his image in fiction (for example, in the 13th-century Romance of the Rose).

He was drawn with a bow and arrows, and his head was decorated with a crown or even a colored halo, which "rhymed" with angel-like wings. Eros could be depicted wearing a mandorla, although usually it only surrounds the figure of God or the Virgin Mary. To show the similarity of love for God and for one's neighbor, Christ was sometimes painted with a coal in his hand (a typical attribute of Cupid, a symbol of passion burning in the heart) or even piercing the hearts of his followers with arrows.

In the Renaissance, these motifs developed. The putti were now painted like Eros - winged babies with halos, who in different contexts could denote the souls of the deceased, serve as an allegory of death and resurrection, as well as act as angels.

In the paintings of Baroque painters, winged little boys dressed in down and ashes resembling putti - older, but with an androgynous appearance, ruddy cheeks, and bare bottoms - play musical instruments.

And in colonial South America, the dapper, fashionably dressed angels were given arquebuses, "enlisting" them as part of God's army. However, the move is not new: already in the Middle Ages, the archistratigus of the heavenly army, the Archangel Michael, was depicted in full battle garb and with weapons.

Arman ("He is a dragon", Russia, 2015)

Arman is a dragon-werewolf, naturally, extremely cute and sexy. Also, half-naked - where have you seen dragons in pants? Only a loincloth, only hardcore! The plot is obscenely simple: Arman wants to perform an ancient ritual for which he kidnaps a beautiful girl, but his human essence gets out of hand and he falls in love with his captive. What follows is a ritualistic teenage dance around each other worthy of Twilight, and at the end - suddenly! - a happy ending! Hooray! Hooray!

Angels of Art Nouveau.

During the Classical period, artists extolled the image of the majestic messenger of heaven, ranging from an antiquated languid young man in a toga to a brutal knight. Suddenly, however, a new character appeared - a female angel: she was portrayed both as a reserved lady, in the spirit of the time, and as a charming winged beauty.

Now this image looks absolutely natural, but before the Victorian era it would never have occurred to anyone to draw a heavenly messenger in such a way. Most likely, such a type appeared as a result of a mistake by artists who often saw a similar soul figure with wings in cemetery sculpture and did not pay attention to the context of traditional sacred art.

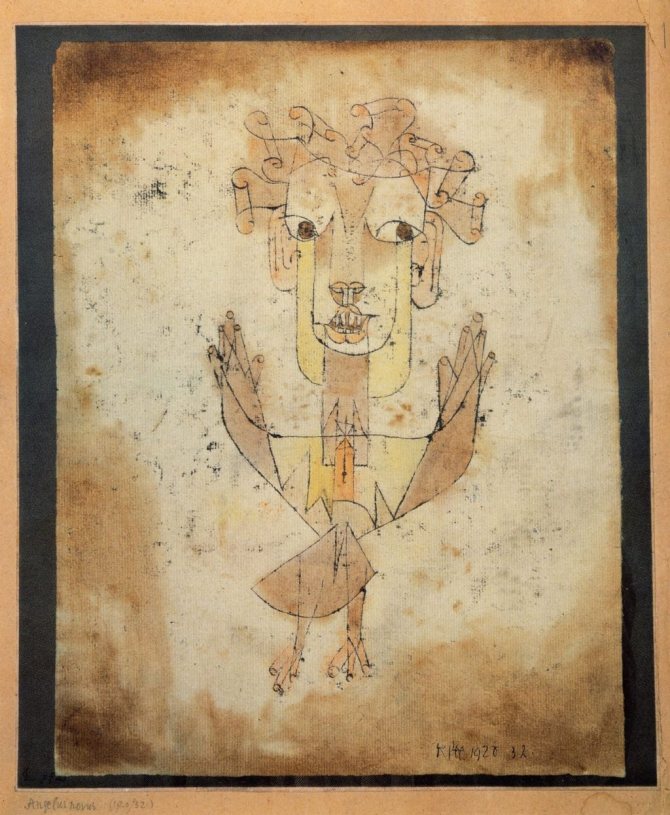

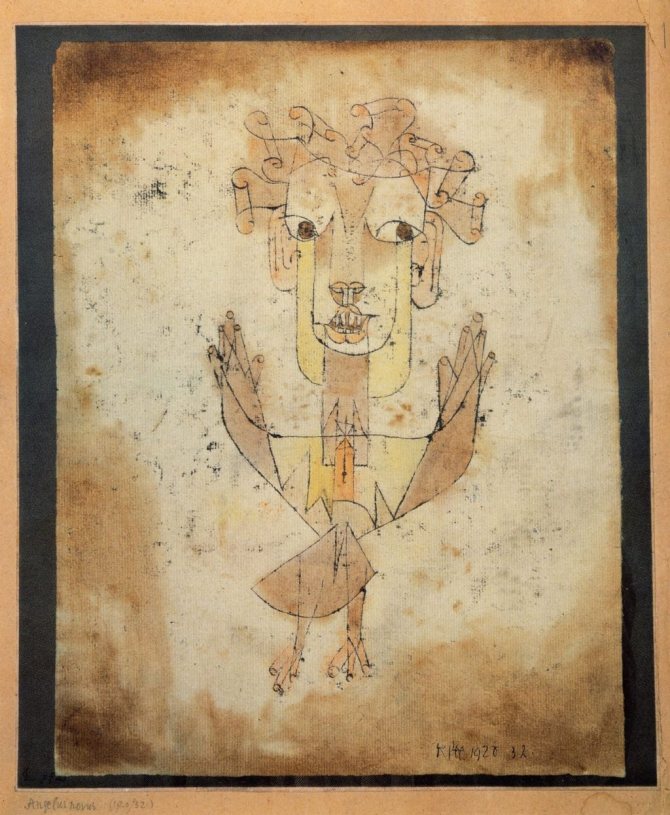

But in the twentieth century this stereotype was broken as well. Dali, Picasso, Kandinsky and Chagall painted heavenly messengers who invariably added to the already enlarged body of God over two millennia. But perhaps the most famous image in this series was created in 1920 by the German artist Paul Klee. His Angel of History served as the starting point for philosopher Walter Benjamin, who offered his interpretation of world progress. He saw in the unusual figure with his hands raised up, as if at gunpoint, not good news, but a prophecy of disaster and the destruction of the familiar order by inhumane war:

"This is what the angel of history must look like. His countenance faces the past. Where for us is the chain of events to come, there he sees a solid catastrophe, incessantly piling ruin upon ruin and piling it all at his feet. He would have stayed to pick up the dead and blind the wreckage. But the squall wind rushing from heaven fills his wings with such force that he can no longer fold them. The wind carries him irresistibly into the future, to which he has his back turned, while the mountain of rubble in front of him rises to the sky. What we call progress is this flurry."

There are several images of angels in popular culture today. The type of heavenly warrior, which dates back to medieval art, has become popular, and can now be found in fantasy literature and computer games. Not infrequently the messenger also appears as a beautiful woman, as if she had descended from a picture by the Pre-Raphaelites. The wingless beardless angel, the many-headed chimera angel and the chubby Eros angel - the merciless wind of artistic progress is taking them further and further into the past, which is now remembered only by art historians and interested people like you and me.

Michael the Archangel (Legion, USA, 2010)

Paul Bettany always gets minor unsightly roles of henchmen of the main villain or, on the contrary, the head of the search team, which is looking for the main villain. But in the movie "Legion" this historical injustice has been corrected: Bettany plays neither more nor less, but the defender of mankind, literally its last hope. The movie sucks, to be honest, but Handsome Paul is half the time wearing wings and half-naked. It's worth putting up with for the sake of it.