Veni, Vidi, Vici. Once upon a time the army of Pharnaces II, king of Pontus, positioned itself on a hill near the city of Zele. VENI (Came). Caesar, tired of waiting until Farnacus, unwilling to admit his defeat in the civil war, withdrew his army to Pontus and fulfilled the terms of the treaty, lost his patience and immediately joined his army with the remnants of the unit previously defeated by the intransigent king. VIDI (Seen). The great emperor, through the eyes of an experienced warrior, saw the neighboring hill left unattended by the Pontic army and occupied it, cutting off the enemy's escape route.

VICI (Victory).. After 4 hours of battle, the army of Pharnaces, trapped by Caesar's army in a narrow valley between the hills, turned to flight. "Veni, Vidi, Vici," Caesar wrote to the Roman Amantius. Three of these short words encapsulate the great talent of the general and the victory that occupied a special place in the history of Rome. Modern man has supplemented this beautiful aphorism with meanings of the meaning of life, the pursuit of self-improvement and achievement of purpose.

"Latin is out of fashion nowadays, but if I tell you the truth..."

In A. С. Pushkin, Latin only "went out of fashion," although its knowledge characterized a person only on the best side. But even then it had long since lost its status as a spoken language. But even if we omit its fundamental role in medicine, especially in pharmacology, we can state that Latin quotations and expressions will live on for centuries. Jurisprudence is also quite difficult to do without the help of Latin, the name of which was given to the region in Italy - Latium, the center of which is Rome. Latin sayings serve not only as a decoration of language, but sometimes these phrases alone can express the essence of an issue. There are and are in demand collections of Latin winged expressions. Some phrases from them are familiar even to people who are far from Latin and science in general.

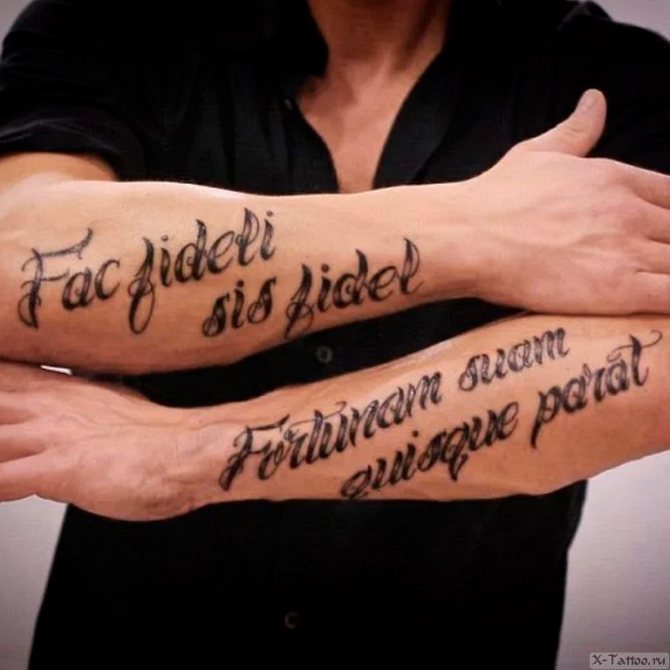

Men's designs

Men usually apply tattoos to the hand.

Less often, for the application of the phrase use areas of the body:

- chest;

- back;

- ankle.

The part of the body to beat the tattoo is chosen based on the meaning that the future wearer wants to show.

Phrase-Pearl .

First of all, such quotes include the greeting "Ave!" and the sacramental "Veni, vidi, vici." Dictionaries and reference books rely on the testimonies of Greek and Roman philosophers and historians, such as Plutarch's "Sayings of Kings and Commanders," from which the phrase was derived. The high culture of the ancient Mediterranean, the "cradle of civilization," is laden with beautiful legends. Famous kings and generals who were intelligent and educated are attributed bright sayings, and if they are not long and beautiful, they are capacious, short and precise.

The phrase "Veni vidi vici" belongs to Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.). It meets all standards of historical catchphrases - elegant in style and appearance, clever and, most importantly, it was fully in keeping with the events of the time.

Veni, vidi, vici

Caesar's in Egypt had only a thousand soldiers, but at the end of the summer the good news reached Rome: the arrogant Pharnaces, son of Mithridates, who had so frightened the Eternal City 20 years before, was defeated and fled into the wild steppes of Scythia. It became known that a Roman citizen, Matius, received a letter from Caesar with only three words: "veni, vidi, vici." "I came, I saw, I conquered" in Latin.

What was behind this message? It is known that the Roman detachment traveled a great distance at lightning speed to join up with its comrades previously defeated by Farnacus. The legion's swiftness and organization gave birth to the first word of the winged phrase - veni. The opposing armies converged on the Pontic fortress of Zela.

In the science of war there is such a concept as "evaluation of the situation": the commander calculates the enemy's weaknesses and strengths, its armament, fighting spirit, the terrain on which his soldiers will have to fight. The commander must see the battlefield through the eyes of the warrior. And Caesar did. Literally: the Pontic infantrymen, having occupied the dominant height, left the neighboring hill unattended. At night the Romans climbed it and began to prepare fortifications. Farnacus was now unable to retreat and could not use his main weapons - chariots and heavy cavalry. Caesar's commanding talent gave a second word - vidi.

The word Vici in Latin means victory. Despite the fact that the Roman legions were lined up on the slope of a high hill, Farnacus decided to defeat them. The Pontians led the attack along a steep ridge. They succeeded in pinning their enemy to a fortified camp, where a fierce battle ensued.

For a long time it was impossible to say who would have the battlefield. It even seemed that the army of Farnacus was defeating the Romans. But the veterans of the VI Legion, holding the right flank, overturned the attackers and turned them to flight. The Pontians were only able to delay the enemy, giving their king an opportunity to leave the scene of the battle. The combination of the bravery and skill of the legionaries, with the talent of their commander, made up the last part of the slogan veni, vidi, vici - victory, victory, vici…

The following factors accounted for the success of the Roman legions:

- The presence of experienced "veterans" who turned the tide of the battle.

- The successful position chosen by the commander.

- Confusion in the enemy camp, intensified as a result of crushing in a narrow space.

Events preceding the appearance of the phrase

Caesar was not having the best time of his career. The huge, well-armed army of Pharnaces, son of the defeated Roman dictator Mithridates, landed in Asia Minor and began to win one victory after another. The son avenged his father. Julius Caesar could not return to Italy, where urgent matters called him, leaving everything as it was. And so in 47, at the end of the summer, at the town of Zele, led by a brilliant commander troops completely defeated the army of Farnacus. Victory was easy and swift, Caesar returned to Rome a triumphant. He immortalized this brilliant event with a letter to his friend Aminius, in which this phrase was written.

"I came, I saw, I conquered" (Battle of Sele, August 2, 47 B.C.)

The summer of 47 B.C. was an anxious time in Rome. Bad news came from everywhere. In Spain, Illyria and North Africa the flames of civil war, almost extinguished after Pharsalus, were again blazing. Serious unrest broke out in the city itself, caused by the agitation of Dolabella, who called for the cashiering of debts. Veteran riots broke out in Campania and elsewhere in Italy. Mark Antony, appointed deputy dictator and effectively in charge of the state, handled the situation poorly, rapidly losing credibility.

In addition to all the troubles, Rome broke the news, which brought to mind recent, not the best episodes of its own history. Pharnaces, son of Mithridates Eupator, had landed in Asia Minor, defeated the army of the Roman governor Domitius Calvin at Nicopolis and, having established himself in the Pontus, began to restore his father's power. Grim shadows of the past seemed to rise. Mithridates Eupator had not been forgotten in Rome, and now that a formidable avenger had appeared, one must have wondered that Pompey Magna, the victor of the Pontic king, was no longer alive.

Meanwhile, Caesar, who had been reappointed dictator and, therefore, responsible for the security of the state, had been in Egypt for a month already, where conflicting, but very unfavorable news for the Farsalian victor was coming from. The war was going on at a sluggish pace, with varying success. Caesar's luck seemed to have run out. The main point, however, was that the Egyptian campaign was being waged for interests completely incomprehensible to the average Roman. Rumors that the aging dictator was personally sympathetic to the young Egyptian queen persisted. They only intensified after Caesar, not without difficulty, confirmed Cleopatra on the throne and went with her on a two-month journey along the Nile.

So Caesar had to return to Italy. Business could not wait. But the great connoisseur of politics understood that a mere return from Egypt would immediately raise a host of perplexing questions and reproaches. The victor's laurels had withered away. What was needed was success - a quick, impressive success that would make him forget the Egyptian adventure. So Caesar might well have thought Farnacus had been sent to him by fate. To defeat the son of the formidable Mithridates - what could make him forget his failures and miscalculations sooner?

And so at the end of the month, which has not yet been named August. 1

, joyful news spread through the Eternal City: Farnacus was defeated. Once again Caesar's luck returned - the victory was not only complete, but also easy and quick, gained as if on the spot, without much effort.

A great master of political propaganda, Caesar took full advantage of his success. In a letter to one of his friends, Matius, he dropped the polished phrase, "Veni, vidi, vici," which immediately became a winged phrase. Or rather, Caesar's friends tried to make it so. The expression quickly became so well known that after Caesar's return it was written on the shield carried during his Pontic triumph. The aureole of the victor returned to the dictator; now it was easier for him to restore order to Rome, reassure disgruntled soldiers and continue the war with the Republicans. The phrase from the letter to Matius remained for centuries a symbol of swift and decisive success.

This textbook story is mentioned with more or less completeness by all those who recount the events of the civil wars 2

. But in the friendly chorus praising the victor of Pharnaces there are occasional notes that force us to revisit these events, trying to understand what really lies behind "Veni, vidi, vici".

Caesar made sure that contemporaries remembered more than just the three famous words from the letter to Matius. The triumph over Pharnaces indirectly undermined the position of the Pompeians by diminishing the glory of their late leader. Caesar, therefore, dropped a remark that also became the property of posterity. "Then he often remarked how fortunate Pompey was to have won the glory of a general by victories over an enemy who could not fight" (Plut., Caes., 35). In Appian's version he expressed himself even more explicitly: "O happy Pompey! So, therefore, for that you were considered great and were called Great, because you fought such men under Mithridates, the father of this man!" (App. Bell. Civ., II, 99). The story of the war with Pharnaces was presented accordingly. The same Appian cites the following version, which it makes sense to hear in its entirety, as the most typical of Caesar's apologists:

"When Caesar began to approach, Farnacus became frightened and remorseful of his conduct, and, when Caesar was at a distance of 200 stadiums from him, sent ambassadors to him to make peace; the ambassadors presented Caesar with a golden wreath and, in their folly, suggested that he should become engaged to the daughter of Farnacus. Caesar, learning of this proposal, advanced with his army and marched ahead himself, talking with the ambassadors, until he came to the fortification of Pharnaces. Then he exclaimed: "Will this patricide not receive his punishment immediately?" and jumped on his horse, and already at the first attack turned Farnacus to flight, and killed many of his army, although Caesar himself had only about a thousand horsemen, who ran out with him first to attack." (App. Bell. Civ., II, 91).

So, Caesar, if this version is to be believed, showed the best qualities. He is brave, cunning, lucky and even able to take revenge on the murderer of his father, that is to say, to avenge the death of one of Rome's most fierce enemies, Mithridates! The noble hero is opposed by a cowardly, narrow-minded and weak opponent, who, moreover, is stained with the filth of patricide. To top it all off, Caesar the victor is shown attacking the enemy on horseback at the head of a cavalry detachment - a picture that begs to be painted on a fresco or a painting. It is not surprising that under the impression of such accounts the Romans, forgetting their recent fears, laughed at the sight of the image of Pharnaces displayed in a triumphal procession (App. Bell. Civ., II, 101).

The apologetic version, only in an abridged version, is also given by other authors (Suet., Caes., 35; Liv., Epit., 113; Plut., Caes., 50). Suetonius, however, drops a strange phrase: "In the Pontic triumph they carried an inscription with three words among the others in the procession: "I came, I saw, I conquered", by which he (Caesar - A. S.) marked not the usual war events, but its rapidity" (Suet., Caes., 37). The phrase is obscure, but meaningful. What could the author have meant? Most probably that what Caesar was most successful in defeating Farnacus was its swiftness - he defeated the enemy on the fifth day, four hours after meeting the enemy (Suet., Caes., 35). As for the events of the war itself, Suetonius does not seem to have thought they could be a pretext for special enthusiasm. Even without other sources, simple logic tells us the answer. First of all, Caesar did not bring the victory to a logical conclusion. The patricide and murderer of Roman citizens, the traitor and oath-breaker Pharnaces was not destroyed, but safely evacuated the remnants of his troops, apparently with Caesar's own consent (App. Mith., 120; Cass. Dio, XLII, 47). The success at Zela was not secured.

True, fate punished Pharnaces by appearing in the form of Asandrus, the rebellious governor of Bosporus. But in this case the real victor of Pharnaces is not Caesar, but Asandrus! So, the victor ended the war not in the Roman tradition - with such an enemy as the son of Mithridates, it was not supposed to conclude any agreements, especially after victory. At best, Farnacus could expect unconditional surrender and forgiveness in the spirit of Caesar's policy of "mercy."

However, Suetonius may have known something about the details of the campaign that contradicted the apologetic version. That such versions also existed is proved by the most detailed and reliable source on the war with Farnacus, The War of Alexandria.

This work, which chronologically continues Caesar's Notes on the Civil War, was written by a high-ranking officer who had been with the dictator in Egypt. Of course, it was also written to glorify the victories of Caesar and his army. But the author of The War of Alexandria (hereafter simply, the Author), as a professional military man, sought to recount events with all accuracy, following the style of Caesar's own notes. He believed that the facts would speak for themselves. It is true that the author does not follow this rule everywhere, including in his account of the war with Farnacus, but on the whole his account is order of magnitude more detailed and objective than that of other historians. There are two large passages devoted to Pharnaces and his defeat (Bell. Alex., 34-31; 65-78), which will be used below in addition to some other testimonies.

First of all, the author immediately points out that the threat from Farnak was not a small one. His army, which numbered no less than 30,000 men, had a solid core of veterans with whom Pharrank had fought twenty battles (Bell. 3

The author immediately points out that the threat posed by Pharnaces was serious, and his army numbered at least 30,000 men. From other sources we know that the king had mounted detachments of the Syracian and Aorsian tribes allied to him (Strab., XI, 5, 8). The king prepared for the war very seriously, taking into account both the mistakes of his father and the general unfavorable situation of the Roman state, which allowed him to hope for success

4

.

Pharnaces himself proved to be an unblemished military man and diplomat. He acted quickly, decisively, and, when necessary, brutally, while showing tactical flexibility. Landing in Pontus, he quickly occupied Armenia Minor, establishing himself in his father's long-standing possessions. Without touching Roman Bithynia, he struck at Rome's weak allies, the rulers of Galatia and Cappadocia. All this was done so lightning-fast that only after the invasion of Galatia did the governor of Asia, Domitius Calvin, responding to the request of King Deiotar, begin to gather an army. Pharnaces, instantly changing the front and recalling his army from the distant and inaccessible Cappadocia, concentrated his forces against the Romans and Galatians. At first he evaded battle, fearing the three Roman legions that Domitius had at his disposal, entering into long and inconclusive negotiations. Soon, however, the governor of Asia was forced to send two legions to Caesar in Egypt, after which, apparently having misjudged his strength, he himself moved on Pharnaces. Domitius had at its disposal four legions and auxiliary troops, a total of about 30 thousand soldiers. But only one of these legions was Roman. Two legions were sent by Deiotar, one was hastily recruited in Pontus.

Farnack took this into account. His army was noticeably more experienced and numerous. Now the king did not shy away from the battle and, having waited for the Romans at Nicopolis, defeated Domitius in a fierce battle (Bell. Alex. 38-40). Of the four legions of the Roman viceroy one - Pontic - were lost almost the whole, the Galatian suffered great losses and were later reduced to one, only XXXVI Roman legion retreated with few losses (Bell. Alex., 40). The remnants of the Roman army withdrew to the province of Asia, and Pharnaces began a brutal massacre of his opponents in the cities of Pontus. The Roman citizens especially suffered (Bell. Alex., 41; App. Bell. Civ., II, 91).

Such was the situation in mid-July, when Caesar arrived in Cilicia. Business was calling him to Italy, and he could count only on a lightning successful campaign. The first serious defeat could have put an end to his entire political career. But the task was more difficult than it probably seemed at first. Caesar had few troops. From Egypt he brought one VI-th legion with less than a thousand men (Bell. Alex., 69). We had to count on surprise, maneuver, the experience of veterans and, of course, luck. Caesar simply had no other option.

The small army marched through Cappadocia to the borders of Galatia. Here Caesar was met by Deiotar, who had received forgiveness for helping Pompey and handed the Roman general one legion and horse units. Apparently by this time two legions from Domitius had arrived. Caesar now had four legions in addition to the auxiliary Galatian cavalry: the VIth, the XXXVIth, the Galatian, and another that was probably also Galatian 5

. Considering that the latter three suffered losses at the battle of Nicopolis, and the VIth was little more than a cohort, the Romans had a total of no more than 15,000 to 16,000 infantry and some cavalry. Besides, all these units, except for Caesar's veterans, were composed of new recruits and were demoralized by the recent defeat (Bell. Alex., 69). It is true that Farnacus also suffered losses, his army having been forced to cover a large area. So the king could scarcely now gather all his forces into a fist, but in any case his army outnumbered the Roman one by no less than 7,000 to 10,000 soldiers, moreover, animated by success.

Farnacus, determined to repeat his successful experience with Domitius, entered into negotiations with Caesar. He sought to buy time, knowing that he was hurrying to Italy. So, giving lip service to the promise to withdraw from Asia Minor, to return prisoners and loot, he bided his time, hoping that the Romans would be forced to leave. "Caesar understood that he was cunning, and by necessity undertook now what under other circumstances he did by natural inclination-namely, to give battle unexpectedly to all" (Bell. Alex., 71). These words of the Author suggest that Caesar was not sure of success, which is not surprising.The other strange thing is that Farnacus broke the main rule of a general: never act according to the enemy's plan. However, this strangeness is only apparent. Fate had been kind to Caesar this time too. Without any intervention from him, Farnacus found himself in an even worse strategic position than his opponent before the decisive battle.

If Caesar rushed to Rome, rightly fearing to lose power, Pharnaces had already ceased to be the ruler of Bosporus. Asandros, whom he had left as governor in Panticapaeum, took advantage of the king's absence and rebelled, hoping that the Romans would appreciate the treason and confirm him on the Bosporan throne. Pharnaces himself was now in a hurry to return home to deal with the rebel, but he could not - Caesar's troops were standing in front of him (Cass. Dio, XLII, 46, 4). The roles were reversed, Caesar could still wait a few days, but for Farnacus every hour counted, so he decided to fight.

Pharnaces positioned his army on a high hill not far from the city of Zela, in an old position once fortified by his father, who had defeated the Roman general Triarius here. The place might have seemed happy. The army set about rebuilding the old fortifications and preparing for battle (Bell. Alex., 72).

Initially Caesar took up a position five miles from the enemy camp. But then, having assessed the conditions of the terrain, he noticed the mistake made by Farnacus. Near the camp of the Bosporan king there was another hill, separated from the one occupied by Pharnaces by a narrow valley. The position seemed very comfortable. Having prepared in advance everything for building a new camp, Caesar at dawn secretly occupied the hill next to the camp of the enemy. Now Farnak could no longer leave without a fight. The Bosporan cavalry, moreover, could not attack the Romans entrenched on the high ground. Only when the sun came up did Pharnaces notice that he was face to face with the enemy. It was August 2, 47 B.C. (Bell. Alex., 73).

The Roman troops, having posted a guard, began to build the camp. But they were in for a surprise: the army of Pharnaces, having left the fortifications, began to line up for battle. Caesar took this to be a mere demonstration to delay the construction of the camp, but had no reaction, laughing at the "barbarian" who, in his opinion, had lined up his troops in excessively thick lines (Bell. Alex., 74).

Further events are so important that we should give the word to the Author: "...Meanwhile Pharnaces, with the same step as he went down the steep valley, began to climb the steep hill with the army lined up for battle.

The incredible recklessness of Farnacus, or perhaps his confidence in his strength, really astonished Caesar. Not expecting such an attack, he was taken by surprise. We had to simultaneously recall the soldiers from their work, give orders to take up arms, bring out the legions against the enemy and line them up, and this sudden turmoil put them in great fear. The ranks had not yet had time to line up, when the four-horned chariots of the king with sickles began to create a total confusion among our still-uncorrected soldiers" (Bell. Alex., 74-75).

The last phrase raises doubts. The battle started on a steep slope, where the chariots just could not operate. However, chariots are also reported by another source (Cass. Dio., XLII, 46, 4), which also mentions the actions of the Bosporan cavalry. Appian, as already pointed out, also implies the actions of the cavalry (App. Bell. civ., II, 91). We must suppose that either chariots and cavalry are a mere speculation, and they did not take part in the battle, or the author does not finish his statement entirely. The chariots could only operate in the valley. There may have been a Roman guard there, but it is possible that the legionnaires, pushing the enemy out of the way, were attacked. However, the overall picture of the battle did not change. Panic broke out among the Romans, and Caesar realized that he had laughed at the "barbarian" too early.

So the chariots attack the Romans. "Behind them comes the enemy infantry, a shout goes up, and the battle begins, in which the natural properties of the terrain help much, but most of all the mercy of the immortal gods, who generally take part in all the vicissitudes of war, especially where all human calculations are powerless" (Bell. Alex., 75). For a professional soldier, as the author was, this last phrase is remarkable. Apparently there was a point at which believing in victory was no longer possible. Farnack's calculation proved correct. The only thing that somehow helped the Romans, except, of course, the immortal gods, was the uneven terrain that did not allow Pharnaces to use cavalry. Obviously, the battle had moved to the hillside, to the unfinished camp.

Caesar's military and political career seemed to be coming to an end. What Vercingetorigus, Pompey and the Egyptians had failed to do, the son of Mithridates Eupator could do. But fate kept Caesar this time too. "When a great and fierce hand-to-hand fight ensued, it was on the right flank, on which the VIth Legion of veterans stood, that the beginning of victory was born. It was here that the enemies began to be driven down the steep slope, and then, much later, but with the help of the same gods, all the king's troops on the left flank and in the center were completely defeated." Squashing, crushing each other, throwing their weapons, Pharnaces' soldiers rushed back into the valley. Caesar's army launched a counterattack. The reserve that was in the camp managed to hold off the Romans for a while, which allowed Farnak himself and part of the cavalry to withdraw. The rest of the Bosporan army was either killed or captured (Bell. Alex. 76).

The author's enthusiastic tone cannot conceal an important fact: The king and part of his cavalry escaped. Moreover, Caesar did not pursue the defeated. Farnacus seems to have bargained for the right to evacuate with the remnants of his army, surrendering Sinope and other cities. However, his imminent doom awaited him in the Crimea after his unsuccessful attempt to reclaim the Bosporan throne from the usurper Asandrus (Cass. Dio, XLII, 46, 4).

So, a victory, though incomplete, was nevertheless won. Caesar was now able to compose his famous letter to Matthias, laugh at his defeated enemy, and celebrate his Pontic triumph. The victors, as we know, are not judged. However, the fate in which the dictator had so much faith, having once again granted him victory, had taught him a lesson. Farnacus, who returned from the battlefield alive, but who died because of the betrayal of the one he had trusted, warned the victor with his death. Caesar, as we know, did not hear or heed this warning. Until the March Ides of 44 B.C. two and a half years remained.

Thus, even from the author's favorable description of Caesar in The War of Alexandria, the victory over Pharnaces was indeed swift, but by no means easy. Caesar made the grave mistake of underestimating his enemy, who managed to bring him to the brink of defeat. The letter to Matius and the scornful words about Pompey's false glory were a tribute to political propaganda, which, not without Caesar's own help, had created an image of the Hero and Savior of the Roman people. In fact, "Caesar, who had so many times won, was exceedingly glad of this victory, for he had very quickly ended a very important war, and the memory of this sudden danger gave him all the more joy, for this victory was easily obtained after the very grave situation in which he was" (Bell. Alex., 77). Probably, after Zela Caesar believed even more in his fate, which kept him even in such difficult circumstances. Indeed, Caesar's credit for the victory over Pharnaces is less than that of his veterans. It was they who defeated the select armies of Pharnaces. The advantage that the Bosporan king was able to secure on the eve and during the battle was negated by the high professionalism and courage of the soldiers of the VI Legion, who managed to wrest the victory. In this it is possible to refer to the opinion of such an expert in military affairs as Napoleon, who estimated the victory over Farnacus exactly as the success of "a handful of brave men" who did the almost impossible in a situation that seemed hopeless 6

.

The phrase from Caesar's letter to Matthias, which was clearly wishful thinking, has remained for centuries. We should not accuse Gaius Julius of insufficient objectivity. After all, great men have their weaknesses too.

(1) The battle of Zele took place on August 2, 47 B.C. (Utchenko S.L. Julius Caesar. - M., 1976. - P. 263). The news reached Rome in 15 to 20 days, considering the summer time, which allowed the use of a speedboat. [back to text]

2. App. Bell. civ., II, 91; App. Mithr., 120; Plin., Caes., 50; Suet., Caes., 35; Liv. Epit., 113; Cass. Dio., XLII, 46, 4; Anon (Caes.) Bell. Alex., 34-41, 69-76. [back to text].

3. Pharnaces' army outnumbered Domitius' army, which had four legions and auxiliary troops, that is, at least 30,000 (Bell. Alex., 34). Part of these troops Pharnaces brought with him from Bosporus, part could have been recruited in Pontus. [back to text].

From the latest works about Pharnaces: Saprykin S. Yu. Mithridatian traditions in Bosporan politics at the turn of AD // Antiquity and barbarian world. - Ordjonikidze, 1985. - С. 63 - 86. Analysis of the Battle of Zela: Golubtsova E. С. Northern Black Sea coast and Rome at the turn of our era. - М., 1951. - С. 56-63. We can agree with the conclusions of the author not in every detail. [Back to text].

5. Domitius had no other troops, and the sources report nothing about a new recruitment. However, this legion may have been formed from the remnants of the Pontic and one of the Galatian armies most damaged in the battle of Nicopolis. [back to text]

6. Napoleon I. History of Caesar's Wars. - M., - PP. 178-187. [back to text].

Publication:

XLegio © 2003

A brilliant saying of a brilliant man.

"Veni vidi vici" is not bragging; it is a statement of an easy, brilliant and very meaningful victory - "I came, I saw, I conquered." Naturally, the phrase went viral instantly, and, according to historian Suetonius, author of Life of the Twelve Caesars, it was inscribed on a banner that was carried in front of Gaius Julius when his victorious army entered Rome. Mountains of literature have been written about Caesar, his popularity is not diminishing but increasing thanks to cinema and salad. He is quoted because the phrase "Veni vidi vici" is not the only expression that has gone down in history. But it has become the exact iconic name for everything that is done on time, brilliantly, without a hitch. And, of course, it, so beautiful, is used as a slogan on the emblems of various firms, the most famous of which is tobacco . The words adorn packets of Marlboro cigarettes.

Julius Caesar was the author of so many phrases - clever, prophetic and cynical. He said that one must not offend guests, that every man is the master of his own destiny, that he, Caesar, did not care whether they hated him, as long as they feared him. Dozens of sayings have been left to posterity, but "I came, I saw, I conquered" is a saying that announces itself. When you read it, you are captivated by it, and you realize that no one has managed to be more precise, cleverer, more elegant in declaring victory.

And who else "came and saw"?

Famous historical figures and writers have repeatedly quoted this popular phrase. "Came, saw, ran" - so commented the defeat of the Duke della Rovere of Milan in 1526 historian Francesco Guicciardini. "Came, saw, fled" - wrote the British on commemorative medals cast in honor of the victory over the Spanish Great Armada. Jan Sobieski, having defeated the Turks at Vienna, sent a letter to the pope with the phrase "We came, we saw, and God won." Joseph Haydn is credited with the humorous paraphrase "I came, I wrote, I lived," while Victor Hugo said "I came, I saw, I lived" in a quite different, tragic sense, as he titled a poem dedicated to his daughter, who died young.

The winged phrase has been used more than once in advertising. Philip Morris, the tobacco brand, has stamped the expression on its trademark and used it in advertisements for Visa cards (Veni, vedi, Visa) and the next version of Windows (Veni, vedi, Vista).