Since the end of the 8th century, the Japanese began using special masks to protect the face. At first, the samurai mask had the simplest versions, which protected the cheeks and forehead of the warrior. Those who did not have the money to buy real armor used these masks for protection as a substitute for a helmet. They were very different from the real battle instances, but nevertheless history counts more than a thousand years of use of this part of samurai armor.

History of the subject matter

Samurai are not only oriental warriors who are skilled in weapons and hand-to-hand combat. The samurai's main meaning lies in his code of honor, called Bushido.

The main meaning of the samurai tattoo is its code of honor, called Bushido. The samurai tattoo symbolizes the presence in a person the qualities that possessed the oriental warriors in the past. In people's minds, the samurai is the analog of the medieval knight from European countries.

However, everything is much more subtle. Choosing from photo sketches such a tattoo is worth considering not media-romanticized image of Japanese warriors, and to know the attitudes and philosophy, following which lived this Japanese class. To understand the meaning of the image of the samurai, you need to know who these people were in the past and gather information about their Bushido code.

Otherwise it was also called "the way of the warrior" and constituted a whole philosophy of life of an elite Japanese swordsman. Each samurai had a lord whom he was obliged to serve to the death and protect his interests. This is one of the basic ideas of Bushido.

In the event of the death of a suzerain (usually the shoguns), his samurai were to take revenge and commit hara-kiri (a method of suicide invented in Japan). In translation, the word samurai means "to serve. Without observing the rules, the samurai would not have gained such popularity in modern society and would have remained in history as petty feudal lords. The basic tenets of Bushido are the following rules:

- live when required to live, and die when required to die;

- speak truthfully;

- moderation in eating;

- no promiscuity;

- keeping one's death in one's soul;

- justice, courage, and loyalty;

- reverence for parents;

- to die with honor, after receiving a mortal wound to speak one's name.

The presence of a portrait of a samurai on a person's body indicates that his life complies with the above rules. According to Japanese culture, the presence of such an image on a woman's body means her loyalty and service to her husband, as well as dedication to her family.

Famous swords

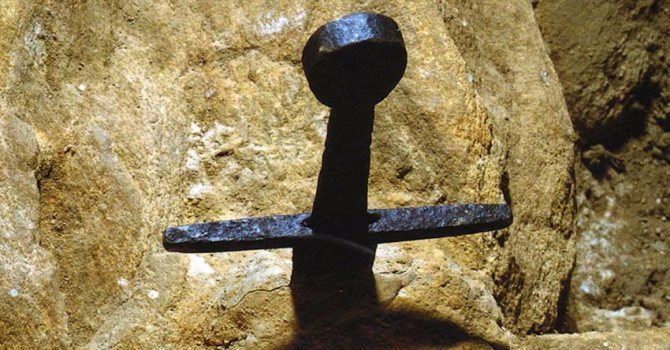

Excalibur, King Arthur's sword (in stone)

Excalibur or Caliburn is King Arthur's magic sword (it is not a historical, but a literary character).

Excalibur is sometimes drawn in stone, although this is incorrect. Arthur carried it with him and used it in battles, and he pulled another sword from the stone, thus proving his right to the throne. By the way, there's another sword in the stone, which we'll talk about a little later.

Excalibur is also depicted in a hand raised from the water. According to the legend, in the last battle Arthur felt that he was dying and asked one of the knights of the Round Table, Sir Bedevere, to return the sword to the Lady of the Lake. A hand rose from the lake and caught the sword that had been thrown.

There are different versions of the sword's origin. According to one, Excalibur was forged by the smith god Velund, and according to another, it was forged on the mythical island of Avalon.

I don't think we've ever had a tattoo of King Arthur's sword. Maybe you could be the first. It can be made realistic, in graphics and even linocuts, with or without Arthur.

Excalibur, King Arthur's sword (in stone)

Excalibur, King Arthur's sword (in stone)

Narsil, sword of Gondor.

The famous sword from Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy, forged by the finest smiths of the dwarves of Middle-earth.

During a duel with Sauron, King Elendil was killed and Narsil is broken. Elendil's son, Isildur, grabbed the fragment of the sword and cut off Sauron's finger with the One Ring (the same one that Golum found, then stole by Bilbo and threw into the volcano by Frodo at the end of the trilogy).

The sword became a symbol of hope and was forged by the elves, receiving the new name Anduril.

Narsil, the sword of Gondor.

Sting. The Sword of Bilbo Beggins.

An elven sword found in the treasury of the trolls.

Sting. The Sword of Bilbo Beggins

This sword helped Bilbo and later his nephew Frodo more than once. For example, in a fight with trolls and the spider Shelob.

Swords from Game of Thrones

Ned Stark's sword was called the Ice. It is a huge broad sword forged in Valyria.

Swords from Game of Thrones

The swords of House Lannister, the "Widowmaker" and the "Loyal Oath", were carried by Jaime the Kingslayer and Joffrey. These swords were forged from "Ice" steel after the execution of Ned Stark.

Swords from Game of Thrones

Swords from "Game of Thrones."

And, of course, Arya Stark's Needle:

Swords from "Game of Thrones"

Sword in Stone.

This sword is linked by legend to the Italian knight Galliano Guidotti, who led a very frivolous lifestyle. One day the Archangel Michael appeared to him and demanded he become a monk. The knight laughed: "A monk with a sword? It's as hard for me to become a monk as it is to drive a sword into a stone." You shouldn't have: the sword went into the stone like butter.

Sword in stone

This sword stone is now housed in the chapel of Monte Siepi.

The Sword of the Apostle Peter

With this sword Peter cut off the ear of a slave during Christ's capture. The sword became a symbol of devotion. Its exact copy is kept in Poznan, Poland.

The Sword of the Apostle Peter

Nanatsusaya-no-tachi

One of the most unusual swords in world history is the seven-toothed Japanese blade.

Nanatsusaya-no-tachi

Durandal

In the French city of Rocamadour, there is a chapel of Notre Dame (yes, yes, Notre Dame is not just in Paris, but in almost every city in France), and in its wall sticks out an old sword. According to legend, it belonged to Roland himself, the hero of a medieval French epic.

Durandal

The sword stuck in the wall after Roland hurled it at the enemy, but missed.

Muramasa and Masamune's Blades

Muramasa was a Japanese armorer and made incredibly sharp and strong blades. His swords are considered cursed, awakening bloodlust: Muramasa's naked blade will not return to its scabbard until it bleeds.

Muramasa and Masamune's Blades

Musamune was also a famous Japanese armorer, but his swords are considered a symbol of equanimity.

Blades Muramasa and Masamune

Juayez

Juayez in French means "Joyful". This sword belonged to Charlemagne, Emperor of the West. It is mentioned in the poem "The Song of Roland," where it is attributed magical properties.

The hilt is said to have been made of a spear fragment belonging to Longinus, the Roman centurion who pierced the crucified Christ.

Jouayez .

The sword is now in the Louvre.

The Sword of Damocles

The Syracuse ruler Dionysius the Elder once offered his favorite, Damocles, who considered him the luckiest of men, to take his throne for a day. Damocles was sumptuously clothed, cajoled and placed on the throne.

During the feast, Damocles saw a sword hanging over his head on a thin horsehair. So Dionysius showed that the ruler was always living on the edge of death.

The Sword of Damocles

The sword of fire

Was given to the angel appointed to guard Paradise after Adam and Eve's expulsion (Genesis 3:24).

Sword of fire

The Sword of the Cloister

A sword of Russian fairytale heroes with magic powers, which made the sword-owner invincible.

Cladenec Sword

Lightsaber

The lightsaber is known primarily from the Star Wars fantasy saga, but was invented by sci-fi writer Edmond Hamilton in the story "Caldar - The World of Antares."

Lightsaber

Samurai Tattoo Meaning

A tattoo depicting a samurai signifies many concepts. As a rule, it symbolizes:

- selflessness;

- strength of will;

- independence;

- devotion to a cause;

- freedom-loving;

- physical strength;

- powerful spirit;

- respect for parents and tradition;

- loyalty.

A body tattoo can indicate a person's choice of a certain path that only he knows. A tattoo on the body directly signifies adherence to martial ideals. In Japanese culture, women were not forbidden to engage in the art of warfare. Girls who mastered the art of warfare were called onna-bugeishi.

List of basic symbols of Japan

The following symbols are generally recognized in this wonderful country of contrasts:

- The national flag;

- National Anthem;

- The Emperor's Seal;

- Tanuki (raccoon dog);

- Taka (many birds of the falcon order);

- Toki (ibis);

- Kinji (green pheasant):

- Japanese stork;

- Neko (cat);

- Mount Fujiyama;

- Chrysanthemum;

- Sakura;

- Japanese dolls;

- Japanese food;

- And, of course, the samurai.

The first three symbols are official, while the rest are a reflection of Japanese culture and ancestral heritage.

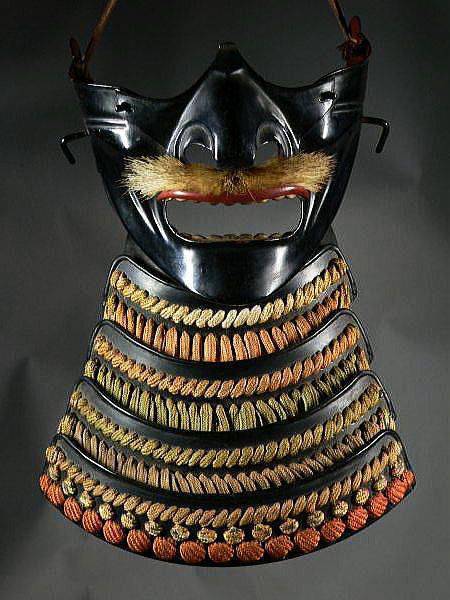

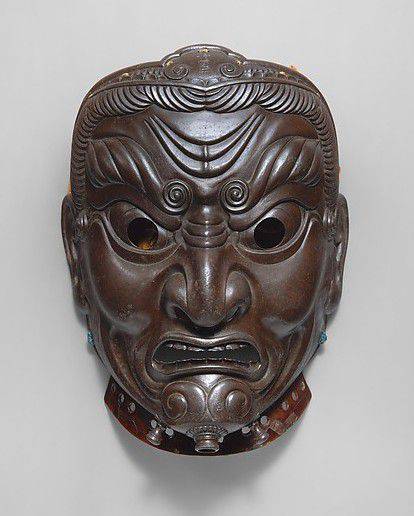

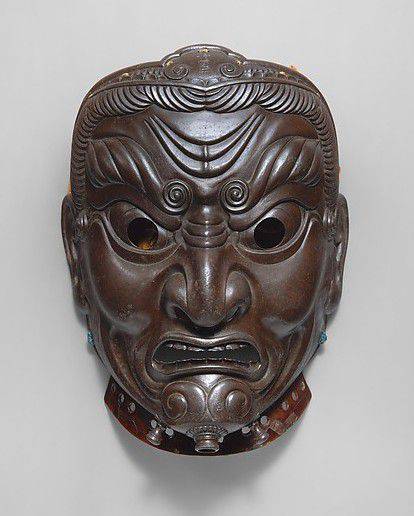

Meaning of the Samurai mask tattoo

A separate type of samurai body painting is the depiction only of their battle mask, which was worn in addition to the helmet. During battles, it was used to protect the face and intimidate opponents.

This is one of the most popular samurai-themed designs. Besides having a semantic message in the tattoo, it is quite exotic looking. The military mask of a samurai was called a mengu. A person who has stuffed such an image on their body declares to those around them that they are on the path of war.

A good drawing of a mengu also means that its bearer is able to overcome difficulties. After all, he is always in a state of full combat readiness.

Kabuto's Helmet and Meng-gu Masks (Part One)

"That day Yoshitsune of Kiso donned a red brocade caftan ... and he took off his helmet and hung it over his shoulder on cords." "The Tale of the House of Taira."

Written by the monk Yukinaga. Translated by I. Lvova

After publishing a series of articles on the armament of the Samurai of Japan, many of the visitors to the VO site expressed the wish that there should also be material on Japanese helmets as part of this topic. And, of course, it would be strange if there were articles about armor, but not about helmets. Well, the delay was due to... the search for good illustrative material. It is better to see once than to read 100 times! So, Japanese helmets... First of all we should note that the helmet was considered by all peoples and at all times to be the most important accessory of the soldier's equipment and why is not surprising, because it covered the human head. The most important thing is that we should not forget that we have always considered the helmet to be the most important accessory of all the peoples and at all times in the warrior's equipment. These include the simplest helmet - a hemisphere with a visor, like the Romans, and a richly decorated chieftain's helmet with a mask from England, burials in Sutton Hu, simple spheroconical helmets and very complex helmets with several plates on rivets, tophelmets of Western European knights. They were painted in different colors (to protect them from corrosion and make them unrecognizable!) and decorated with ponytails and peacock feathers, as well as human and animal figurines made of "boiled leather", papier-mache and painted plaster. Nevertheless, it can be quite proved that the Japanese kabuto helmet to the o-yoroi armor surpassed all other specimens, if not in its protective qualities, then ... in originality and there is no doubt about it!

A typical Japanese kabuto with shinodare and kuwagata.

However, judge for yourself. Even the very first kabuto helmets, which samurai wore with their o-yoroi, haramaki-do and do-maru armor, were quite different from those used in Europe. First of all, they were almost always made of plates, and secondly, they usually never completely covered a warrior's face. Plate helmets were already made in the 5th-6th centuries, but thereafter it became a tradition. The most common helmet had six to twelve curved plates, made in the shape of a wedge. They were joined to each other with convex hemispherical rivets, the size of which decreased from the crown to the top of the helmet. But in fact they were not rivets at all, but... cases, similar to bowlers that covered them. The rivets themselves on Japanese helmets were not visible!

Kabuto view from the side. The convex "bowlers" covering the rivets are clearly visible.

The crown of the Japanese helmet had... a hole called tehen or hachiman-za, surrounded by a decorative rim, a rosette made of bronze tehen-kanamono. It should be noted that a feature of Japanese helmets was great decorativeness, and in these details it showed itself to the fullest extent. The front of early helmets was decorated with strips in the form of applied shinodare arrows, which were usually gilded so that they were clearly visible against the metal strips traditionally coated with Japanese black lacquer. Under the arrows was a visor, called mabizashi, which was attached to the helmet with rivets sanko no byo.

Detail of hoshi-kabuto and suji-kabuto helmets.

The warrior's neck at the back and sides was covered by a shikoro neckpiece, which consisted of five rows of kozane plates that were connected to each other by silk cords of the same color as the armor. Shikoro was attached to the koshimaki, the metal plate that was the crown of the helmet. The lowest row of plates in the shikoro was called hishinui-no-ita and intertwined by cross-lacing. The top four rows, counting from the first, were called hachi tsuke no ita. They ran at the level of the visor and then curved outward at almost right angles to the left and right, resulting in fukigaeshi - "U" shaped lapels designed to protect the face and neck from lateral sword blows. Again, in addition to their protective functions, they were used for identification purposes. They depicted the family coat of arms - mon.

The top three rows of fukigaeshi, facing outward, were covered with the same leather as the cuirass. Thanks to this, stylistic uniformity in the design of the armor was achieved. In addition, the copper gilded ornamentation on them was the same everywhere. The helmet was fastened to the head with two cords called kabuto-no-o. The inside of the helmet was usually painted red, which was considered the most bellicose color.

In the twelfth century the number of plates began to grow and they themselves became much narrower. They also had longitudinal ribs on them, which increased the strength of the helmet, although it did not increase its weight. At the same time, the kabuto was also lined with straps, similar to those now used on helmets for assemblers or miners. Prior to that, the only things that softened the impact on the helmet were the khachimaki bandage, which was tied before the helmet was put on, the eboshi cap, the end of which was straightened out through the tehene hole, and the samurai's own hair.

Suji kabuto of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Before Europeans arrived in Japan, samurai helmets were of two types only: hoshi-kabuto, a helmet with rivets sticking out, and suji-kabuto, with rivets countersunk. As a rule, suji-kabuto had more plates than hoshi-kabuto.

The late 14th and early 15th centuries saw an increase in the number of plates in a kabuto, which began to reach 36 (with 15 rivets per plate). As a result, helmets became so large that they weighed more than 3 kilos, roughly the same as the famous European knight's tophelms, which were shaped like buckets or pots with slits for eyes! Wearing such a large weight on their heads was simply uncomfortable, and some samurai often held their helmet in their hands and used it as a shield to deflect enemy arrows flying at them!

Kuwagata and a disk with a picture of a pavlonia flower between them.

Various helmet adornments were often mounted on the helmet, and most often they were kuvagata horns of thin gilded metal. They are thought to have appeared as early as the late Heian period (late 12th century), when they were "V" shaped and rather thin. During the Kamakura period, the horns began to resemble a horseshoe or the letter "U." In the Nambokuyo era, the horns became broader at the ends. The Muromachi era saw them become exorbitantly huge, and between them they added an upright blade of the sacred sword. They were inserted into a special slot on the visor of the helmet.

Eighteenth-century o-eroy with kuwagata in the style of the Nambokuteo era. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

It was believed that they served not only to decorate the armor and intimidate enemies, but could also be of real help to the samurai in battle: because they were made of thin metal, they partly softened the blows made on the helmet, and acted as a kind of shock absorber. Between them could also be attached the coat of arms of the owner of the armor, intimidating faces of demons and various symbolic images. Often, a round gilded and polished plate - a "mirror" that was supposed to scare away evil spirits - was attached to the visor between the "horns" (and often instead of them). It was believed that, seeing their reflection in it, demons approaching the samurai would be frightened and run away. In the back of the muzzle of the helmet was a special ring (kasa-jirushi no kan) to which a kasa-jirushi pennant was tied, allowing them to distinguish their warriors from outsiders at the back.

In other words, it is obvious that the kabuto helmet was a very decorative and also durable construction, but for all its perfection and the presence of shikoro and fukigayoshi, it did not protect the warrior's face at all. In the East and in Western Europe there were helmets with face masks that functioned as visors, but they were attached directly to the helmet. Later European bundhugel ("dog helmet") and armour helmets had an opening visor, and the visor could be raised on hinges or open in a window-like fashion. That is, in one way or another, it was connected to the helmet, even when it was made movable. But what was the case with the kabuto?

The Japanese had their own protective devices for this purpose, namely the happuri mask and the hoate half-mask, commonly referred to as men-gu. Warriors began to use the khappuri mask under their helmets from the Heian period (late 8th century to the 12th century) and it covered their foreheads, temples and cheeks. For servants, the mask often replaced the helmet altogether. Then in the Kamakura period (late 12th century - 14th century) noble warriors began to wear half-masks of hoate, which covered not the upper but the lower part of the face - the chin, and also the cheeks to eye level. The o-yoroi, haramaki-do and do-maru armor did not protect the throat, so they invented the Nodowa gauntlet to cover it, which was usually worn without the mask, as they had their own cover to protect the throat, called yodare-kake.

A typical mempo mask with yodare-kake.

By the 15th century, meng-gu masks and half-masks had become very popular and were divided into a number of types. The happuri mask was unchanged and still covered only the upper part of the face and had no cover for the throat. The mampo mask, on the other hand, covered the lower part of the face, but left the forehead and eyes open. A special plate, which protected the nose, had hinges or hooks and could be removed or inserted at will.

A seventeenth-century maempo mask.

The hoate half mask, unlike the mempo, did not cover the nose. The most open was the hambo, a half mask for the chin and lower jaw. But there was also the somen mask that covered the whole face: it had openings for the eyes and mouth, and the forehead, temples, nose, cheeks, and chin were completely covered. However, to protect the face, men-gu masks limited visibility, so they were most often worn by warlords and wealthy samurai, who themselves hardly fought anymore.

The somen mask was made by the master Myochin Muneakir from 1673 to 1745. Anne and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Museum, Dallas, Texas.

It is interesting that the same somen mask had a hinge attachment on its central part that made it possible to detach the "nose and forehead" and thus turn it into a more open hoate mask or in common parlance, saru-bo, "monkey's muzzle. Many masks that covered the chin at its bottom had one or even three tubes for sweat and all of them had hooks on their outer surface so that they could be attached to the face with cords.

On the chin was a sweat hole.

The inside of the face masks, like the helmet, was dyed red, but the finish on the outside surface could be surprisingly varied. Usually made of iron and leather, the masks were made in the form of a human face, and craftsmen often sought to reproduce in them the characteristic features of the ideal warrior, although very many men-gu were similar to the masks of the Japanese Noh theater. Although they were often made of iron, they reproduced wrinkles, attached a beard and mustache made of hemp, and even had teeth inserted in their mouths, which in addition were also covered with gold or silver.

A very rare ornament - between the horns of the kuvagat there was a mask with a woman's face.

And here below was this mask!

At the same time the portrait resemblance of the mask and its owner was always very conventional: young warriors usually chose masks of old men (okina-men), but older ones, on the contrary, masks of young men (varavazzura), and even women (onna-men). Masks needed also to intimidate enemies, so very popular were masks of leshikh tengu, evil spirits akuryo, demoness kidjo, and since the 16th century also exotic masks nambanbo (faces of "southern barbarians"), or Europeans who came to Japan from the south.

The author is grateful (https://antikvariat-japan.ru/) for the photos and information provided.

Picture by A. Sheps.

Themes of samurai tattoos

There are many sketches on samurai history. It can take more than one day to study the images in the salon. The tattoo can be both multicolored and black. Also white colors are used.

It is possible to apply a small or large image. Some masterpieces are carried out by applying not one samurai, and a whole group of warriors. The illustration of the dragon and samurai is considered one of the most famous.

Only a master professional can achieve the quality of this finished drawing. After all, his perception will depend on the accuracy of the reflection of small details.

Mystical tattoo options consist not only of images of warriors, but also of Japanese characters. Such pictures are often drawn against the background of the setting sun, and the hieroglyphs are applied close to the samurai.

What is a sword

Let's start with the theory. A sword is a cold weapon with a straight blade. Swords are often referred to as sabers with a curved blade. This is a mistake. In the picture on the left is a sword, and on the right - the famous Japanese saber "katana".

Tattoo sword

Tattoo sword

Location samurai drawings

The image of a samurai in combat ammunition will look best on significant parts of the body. These include the chest, shoulder and back.

Not bad options for placement of tattoos will be its padding on the stomach, leg or hand. Tattoo-masters usually perform work on the application of Samurai in the style of realism, oriental or traditional Japanese style. Before going to the studio to choose a sketch from the photo.

Samurai is a very interesting image. The image looks spectacular. However, before you do, familiarize yourself with the history of Japanese warriors.

Sashimono

Nobori helped identify a large unit, but there were samurai symbols that allowed you to know who a particular warrior belonged to. Small flags called "sashimono" were used to personally "mark" samurai.

The flag was on a special construction behind the samurai's back, which in turn was secured by breastplates. The sashimono bore the coat of arms of the daimyo to whom the samurai belonged. Sometimes the name of the daimyo clan was depicted instead of the coat of arms.