Tattoo in the form of a feather - a common type of natal drawing, which has an unlimited number of possible options, deep meaning and ancient origins of origin. Depending on the design and the characteristic meaning, the image of a feather can be suitable for both men and women. The historical homeland of the feather tattoo is considered to be North America, where the figure had a special symbolism and was common among the indigenous population. Bird attributes adorned homes, clothing and used by shamans in carrying out rituals, personifying kinship, immortality and the power of the elements. Only warriors, chiefs and elders had the right to wear the image of a feather. In many cultures this element represented a symbol of beauty, power, freedom and connection with heavenly spirits. In Christianity, the meaning of the feather was reduced to faith, mercy and contemplation.

From the history of the tattoo

The tattoo of a feather has its origins in the tribes of North American Indians. An interesting fact is that there was no unambiguous interpretation of this tattoo even then. However, the image of feathers on the body was considered a sign of exclusivity. People who wore such tattoos, stood out among their fellow tribesmen by certain merits. Such tattoos were usually given to brave warriors, talented healers and shamans.

The feather tattoo symbolizes the harmony of thunder, air and wind - the three elements that occupy a special place in North American Indian culture. In addition, the feather represented a connection with family and the spirits of the dead. The eagle feathers symbolize the qualities inherent in this magnificent bird, namely courage, coolness and impetuous strength.

The ancient Greeks also used a feather in their system of signs. The symbol represented the harmony of power and beauty. In Christian culture, the three feathers were a foreshadowing of the beneficent. Buddhists, however, viewed this symbol somewhat differently, associating it with mindfulness and compassion.

Types and color meanings of feather tattoos

The main meaning is the bird whose feather is depicted on the body. Before choosing a tattoo sketch, it is necessary to study the essence of each type of feather:

- Eagle - physical strength, fearlessness, masculinity;

- Owl feathers - wisdom, intelligence, protection from evil spirits;

- crane - immortality;

- ostrich - justice;

- Peacock - pride, renewal, love, kindness;

- A feather of the phoenix - rebirth, cyclicality;

- The feather of a Firebird - beauty, attractiveness, mystery.

In addition to the belonging of the feather of any bird, the color of the picture plays an important role:

- red - victory, passion;

- orange, yellow - spiritual warmth, peace;

- green, blue - stability, calmness;

- violet - extravagance, principality;

- white - purity;

- black, gray - severity, restraint.

Modern meanings

Of course, the modern interpretation of the pen as a symbol is somewhat different from the representations of ancient cultures. Among the most relevant we will present the following:

- Lightness, airiness and weightlessness. The most primitive, yet very popular interpretation of the pen tattoo.

- Purity, spirituality, morality. It is this interpretation peculiar to European culture.

- The connection with the spirit world. Such a vision was inherent in the Indians.

- A feather in a dissected form as a symbol of mental suffering and pain.

- A feather depicted together with a bird or a flock of birds signifies the desire for freedom from earthly attachments.

Styles and combinations with other elements

A picture in the form of a feather can be independent, made in a certain style, or part of the tattoo as one of the elements of the overall composition. A certain design of the picture and combination with other subjects gives the tattoo a new meaning:

- infinity sign with a feather - freedom, absence of boundaries;

- dream catcher - air, breath;

- feather and birds - hope, desire for independence;

- a feather cut - pain, loss, mental anguish;

- falling feather - sadness, melancholy;

- a broken feather - destruction of a dream, separation, loss.

Each element changes the initial nature of the subject and brings a different meaning to the tattoo. Feather tattoos, depending on style and size, look beautiful on any part of the body. For men, large drawings located on the arm, back, shoulder, spine are preferred. For women who want to emphasize the beauty of a certain part of the body, medium or small images on the wrist, ankle, neck, neckline are typical. A lot is decided by the design of the tattoo, as well as personal preferences and desires of the person.

Feathers

"A bird is recognized by its feathers." This folk wisdom reflects the scientific fact that a feather is a unique formation found only in one class of animals. In fact, none of the groups of living organisms now in existence have feathers, except birds, and there is no evidence that any extinct group had them.

The role of plumage in the life of birds cannot be underestimated. It is the feathers that create the load-bearing surface of the wing and the streamlined shape of the body that allow birds to fly. Feathers are an excellent insulating and waterproof material, and different coloring and peculiarities of plumage shape carry information about species and sex of birds, thus playing an important role in intraspecific and interspecific communication.

Bird feathers originate from the scales of reptiles and also consist of horny substance. They, like reptile scales, are derived mainly from the surface, epithelial, layer of skin (epidermis), and consist of dead and highly modified cells.

Many feathers - good and different

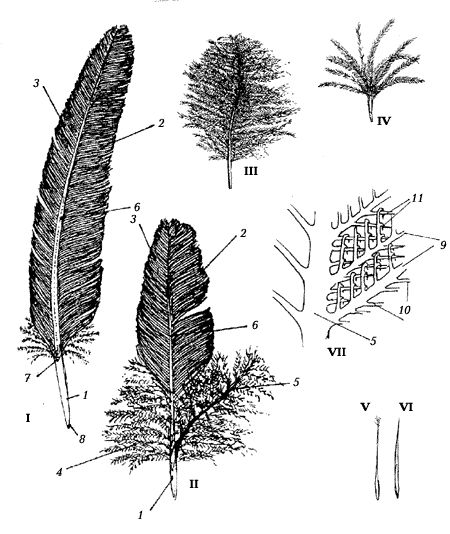

Several types of feathers are distinguished by structure: contoured, down, filamentous, down and bristle feathers.

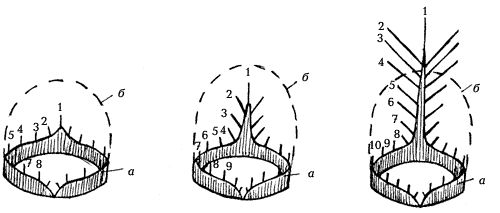

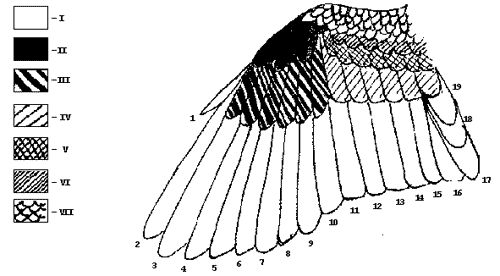

Fig. 1. Structure of a feather and types of feathers. I, II - contour feathers; III - down feather; IV - down; V - filament feather; VI - bristle; VII - diagram of the structure of a contour feather under high magnification. 1 - purlin, 2 - inner part of the feathering, 3 - outer part of the feathering, 4 - downy part of the contour feathering, 5 - shank, 6 - side (supplementary) shank, 7 - upper feather navel, 8 - lower feather navel, 9 - first order beards, 10 - second order beards, 11 - hooks

Contour feathersare probably the most familiar to the reader (Fig. 1, I, II). They cover the entire body of a bird, form wings and tail and create a characteristic "bird" appearance. Outwardly, the contour feather is subdivided into a rod in the axial part and a plumage (Fig. 1). The lower, free, part of the rod is called a cleat. It has an inner cavity that is filled with spongy tissue. At the lower end of the ochin the cavity opens with a small hole - the lower navel of the pen, and at its upper end on the border with the opachal there is, respectively, the upper navel (Fig. 1, 7, 8). The stem in the area of the opalescence is more dense in structure, has no inner cavity, and its core is formed by keratinized cells filled with air. The opal itself is formed by small "offshoots" - first-order beards (Fig. 1, VII, 9) that branch off to either side of the rod. They are so closely interconnected that they form an impression of a continuous surface. But if you look closely, or, even better, put the contour pen under a binocular microscope, you can see that from each of the beards of the first order in rows on both sides depart smaller beards, called second-order beards, or boles (Fig. 1, 6). If we examine this area under even greater magnification, we will find a number of small hooks on each beard of the second order. It is with their help that neighboring beards are interconnected, as a result of which a continuous plate is formed (Fig. 1, VII).

Structure of down feather similar to the structure of the contour feather, with the only difference being that the beards on down feathers are soft, devoid of hooks, and therefore the first-order beards are not interlocked with each other. There is an assumption that feathers with unlinked beards are more primitive than contoured feathers, and as an indirect confirmation we can cite the fact that the featherless birds (a rather ancient assemblage that includes African ostriches, casuaroids, nandu and kiwi) have no feathers with linked beards at all.

The down differs from down feathers in the absence of a shaft - its feathers, also unbonded, depart directly from the ochin.

Due to such a structure of beards feathers of these two types play the role of a "coat" keeping a motionless layer of air near the skin. In many groups of birds (e.g. hens, owls, pigeons) an additional (side) rod, which departs from the rachis of a contour or down feather, serves the same purpose. It is always much shorter and thinner than the main feather and bears soft beards, as on a down feather. Loose beards are often present in the lower part of the down feathers of the contour feathers, which also increases body insulation. In general, all intermediate stages between the contour feathers and down feathers are possible.

Interestingly, temperate species have a higher proportion of down feathers and down in their plumage than tropical species. If a bird has winter and summer plumage (e.g., many grouse), the number of unbound "down" beards in the winter plumage increases, sometimes occupying almost the entire plumage. The "accessory feathers" are better developed in winter in this case. In winter, even the number of feathers in sedentary birds of the middle belt increases - mainly due to down, which "sprouts" by winter.

The filamentous feathers and bristles have the simplest structure and consist only of a shaft, thin and soft in the filamentous feathers and rigid and elastic in the bristles. The scutellum is reduced, and only a few furrows are preserved at the end of the filiform feathers. The filiform feathers serve for touch (responding to the movement of air currents) and grow throughout the bird's body. Bristles can be found in many species at the base of the beak, where they also have a tactile function, and in goatcatchers, swifts, flycatchers and other birds that grab prey on the fly, they "enlarge" the mouth opening. In many birds, the bristles grow along the edges of the eyelids to form cilia.

Some groups of birds (herons, some gobblers, bustards, parrots) have pudenda - areas with permanently growing down, the tops of which are easily broken off, forming a fine powder - "powder". They are usually located on the sides of the chest or on the loins. With its claws, the bird spreads "powder" over the entire plumage, which presumably increases the water-repellent properties of the plumage.

Life course of a feather - childhood, adolescence, adolescence

The skin of vertebrates consists of two layers different in structure and origin: the epidermis and the dermis (also called cutis, corium, skin itself). The epidermis is on the surface and belongs to the epithelial tissues, while the dermis is a connective tissue. Accordingly, in its origin, the epidermis is a derivative of the ectoderm of the embryo, and the dermis is a derivative of the mesoderm. The epidermis of vertebrates is multilayered; the cells of the outer layers are gradually filled with horny substance, die off and slough off, while the epidermis is constantly renewed due to the constant division of its lowest cell layers (the so-called growth layer). The main function of epidermis is protective, and it is the ancestor of a number of skin formations in vertebrates (besides feathers, these are claws, hair of mammals, antlers of deer) and skin glands (sebaceous, sweat, milk glands). Derma is rich in blood and lymphatic vessels and provides nourishment of epithelial tissue, growth and development of its derivatives.

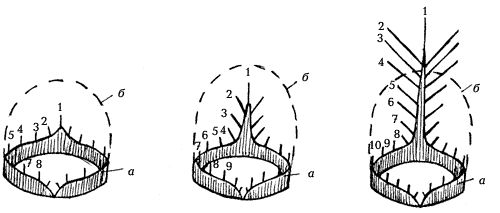

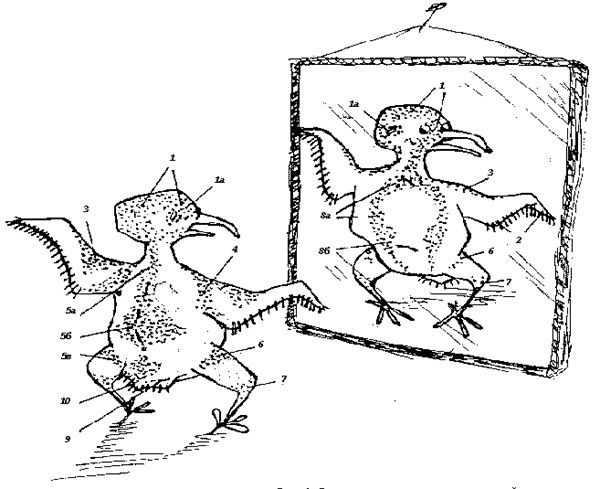

Fig. 2. Scheme of down feather development: A - stage of feather papillae; B - stage of tube (beards develop inside the sheath); C - stage of sheath rupture. 1 - epidermis, 2 - derma, 3 - feather tufts, 4 - sheath, 5 - ochin cavity, 6 - feather pouch

As a result of proliferation of epidermis and dermis cells, a tubercle similar to the rudiment of reptile scales is formed on the skin, which gradually grows in the form of a posterior directed growth, and its base gradually deepens into the skin, forming later the feather pouch. From above, the outgrowth is covered with epidermis; under it, there are living, rich in small blood vessels, tissues of the dermal layer, which form the feather papilla (Fig. 2, A). As they grow, they stretch the feather outgrowth in length, the epidermal layer gradually keratinizes, and the outgrowth itself becomes tube-shaped. At the outer end of the feather tube, the epidermis stratifies: its outer thin layer separates as a conical sheath, and feather beards are further differentiated from the inner epidermis layer. In the case of contour feather development, a row of parallel horny ridges is formed at first, one of which, the thickest, later becomes a rod, the others as they develop move to it (Fig. 3), turning into first-order beards, on which second-order beards develop. During the development of down, the rod is not formed, and all the parallel ridges subsequently become down beards of the first order. All development of the feather occurs within the sheath.

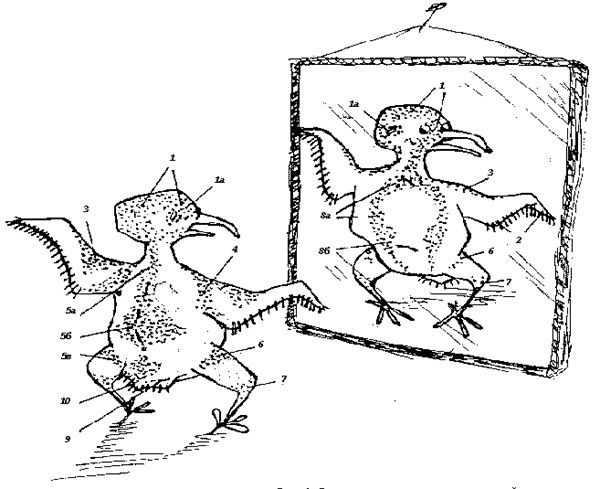

Fig. 3. Schematic of contour feather development: a - sprouting layer; b - sheath; 1, 2, etc. - ordinal numbers of epidermal folds - future first-order bursae

As the feather grows, the living nourishing cells of the papilla die off, starting at the end of the feather tube, the sheath at its end is torn and the feather beards come out, forming a kind of feather tassel. Usually, after the sheath ruptures, feather growth continues at the base, and the young feather at this stage is considerably shorter than it should be. It reaches its final length when the sheath is completely released from the sheath, the remnants of which, in the form of thin films, remain at the base of the ochin for a few more days.

The feather is held in the skin by the tightly fitting walls of the feather pouch and the muscular bands that ensure its mobility.

Feathers do not grow there...

Speaking of feathers, of course, it is necessary to point out that in most birds the contour feathers do not grow as a continuous layer over the entire body surface, but only in separate areas, which are called pterilii (from the Greek pteron - feather and hyle - forest). On the contrary, the areas without feathers are called apteria.

The down feathers grow together with the contour feathers on the pterillia. The down may either cover the entire body of a bird relatively evenly (in paddlefoot, goosefoot, many diurnal raptors, etc.) or be only on the apteria (herons, owls, many passerines). Less often it grows only together with the contoured plumage on the pterillae (tinamu). Only some representatives of the class, such as penguins, palamedays and birds of the keelless group, have a body uniformly covered with feathers, without apteria.

The presence of apteria allows a bird not only to "save" on plumage (the body is covered with fewer feathers). Paradoxically, birds with apteria have better thermoregulation. Probably everyone has seen a feathery crow or a bird on a branch in winter or watched a wavy parrot falling asleep in its cage - its feathers are lifted, bunching up in all directions and the bird looks like a fluffy ball. It is the presence of apteria that gives more opportunities for feather mobility, thus increasing the loose plumage and the thickness of the air cushion, and this, in turn, helps to keep warm.

Fig. 4. Scheme of the arrangement of the main pterygiums on the bird's body: 1 - head pterygium, 1a - ear section, 2 - wing feathers, 3 - wing pterygium, 4 - shoulder pterygium, 5 - dorsal pterygium, 5a - cervical section, 5b - dorsal section, 5c - sacral part, 6 - femoral pterygium, 7 - tibia (leg) pterygium, 8 - ventral pterygium, 8a - thoracic part, 8b - ventral part, 9 - caudal pterygium, 10 - rudder feathers

Despite the fact that the location and shape of the pterygiums are somewhat different and may even be a systematic feature, the location of the main pterygiums on the body of birds is similar (Fig. 4). They are easy enough to distinguish when examining the bird - these are the dorsal, thoracic, brachial, femoral, and cervical pterygiums. Even a novice naturalist can easily find the auricular and anal pterylias among the smaller pterylias. In addition to the auricular pterygium on the head of birds, quite a large number of small pterygiums can be found that only narrow specialists in morphology and molting can understand. And since most readers, after all, are not them, we will limit ourselves to the general name of all pterilliums of this part of the body (incidentally, very often used) - the head pterillium.

Tail and wings

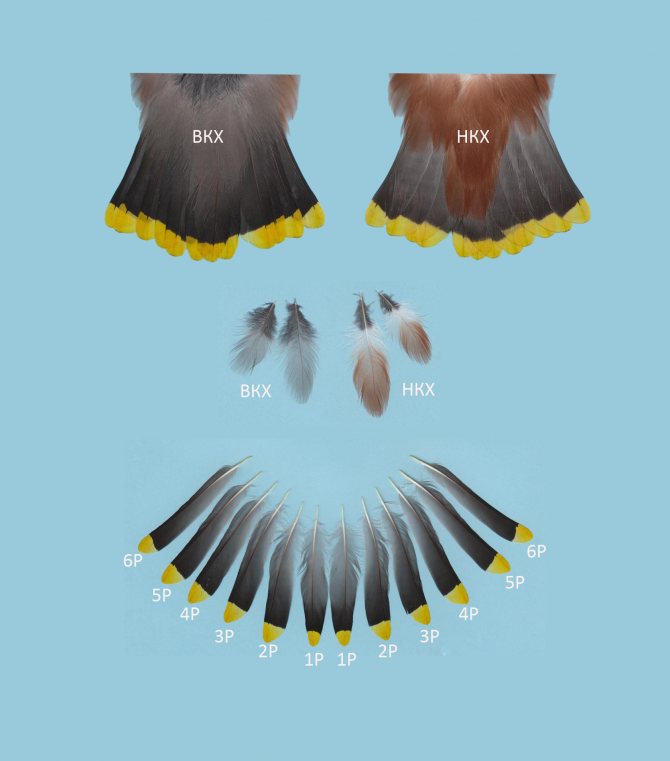

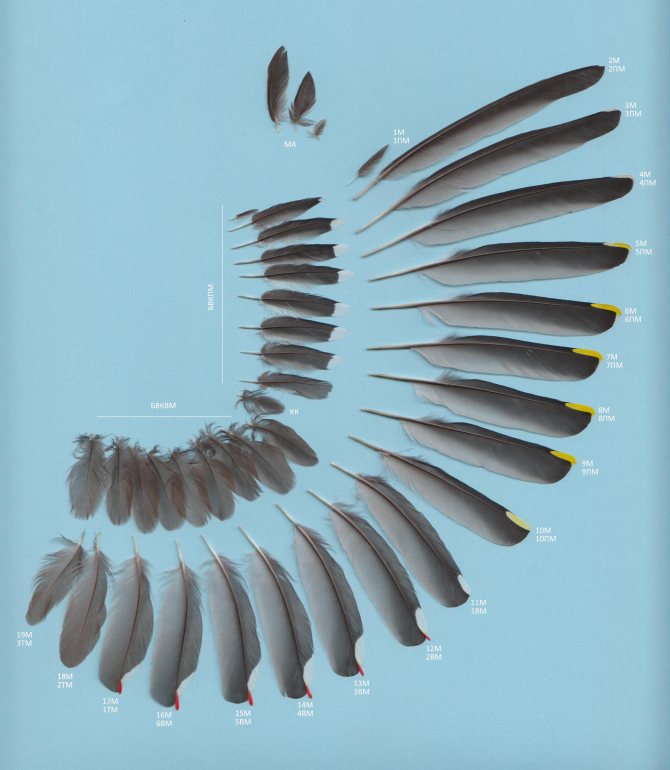

The plumage of wings and tail is worth talking about separately. The large feathers that form the tail itself are called rudders. They are distinguished by the fact that their outer and inner scutellum are more or less the same width. The feathers covering the rudders at the top and bottom are called upper and lower tail feathers, respectively.

The number of rudders varies from species to species. Most often they are 12, but may be from 8 to 28 (in some waders), in passerines of our fauna - 12 (hereinafter this order will be mentioned separately, because it includes about half of the species of our avifauna). The numbering of rudders is from the edge of the tail to the center (in the same direction they are replaced during molting in passerines).

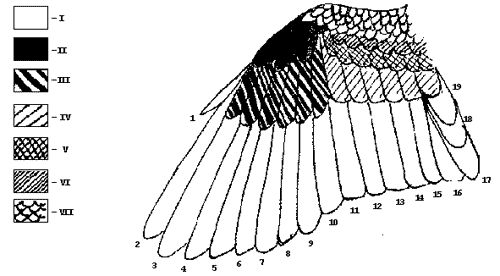

In contrast to the rudders, the feathers that form the supporting plane of the wing, called the winglets, are clearly asymmetrical: their outer edge of the winglet is much narrower than the inner one, and the winglets often have a prominent notch on the outer winglet. A distinction is made between primary (attached to the posterior surface of the hand skeleton), secondary (attached to the ulna), and tertiary (attached to the humerus and usually located one above the other on the wing) wing feathers. Also, these feathers can be distinguished from the steering feathers by some concavity, which provides the wing with better aerodynamic qualities in flight. Apart from the wing feathers, there is also a winglet, several feathers attached to a single phalanx of the first finger, which prevents air turbulence in flight (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Wing feathers - top view (by the example of a representative of passerine species). I - winglets: 1-10 - paramount, 11-16 - minor, 17-19 - tertiary; II - winglets; III - outlines of paramount; IV - large upper outlines of minor; V - middle upper outlines of minor; VI - small upper outlines of minor; VII - outlines of upper arm

The number of primary tibiae is usually 9-11, in passerines of our fauna it is 10. The number of second tails varies in different groups from 6 (hummingbirds, passerines) to 40 (large albatrosses). The number of tertiary pinnipeds also varies greatly; passerines usually have 3, except for the families Orioles (4) and Rooks (4-6). The numbering of the wing feathers is taken from the outer (distal, scientifically speaking) edge of the wing toward the body. It can be either solid, in which case separate groups of primary, secondary, and tertiary feathers are not distinguished, or, if the boundary between primary and secondary is easily distinguishable (for example, in representatives of the passerine species), each group can be counted separately, again starting from the distal end. That is, if you want to indicate the coordinates of your favorite amadine's dropped out fly feather (the thirteenth one from the wing edge), you can write it down simply as the 13th fly feather or as the 3rd minor fly feather. The task is somewhat complicated by the fact that all birds have a shorter first primary wing, and in many groups it is strongly reduced, sometimes falling to almost nothing (e.g., skylarks, swallows, wagtails, buntings, etc.), and you can just not notice it. This is why ornithologists have agreed to count from the first complete wing feather, counting it as the second.

As on the tail, the wing has upper and lower frons. Above the secondary wings, the upperspreading feathers usually form three distinct rows: the first row above the wings are the large upperspreading feathers of the secondary wings, the middle ones above them, and then the small ones. Behind the small ones are the small feathers, which are collectively called the propatagium, or, more simply, the upper arm feathers.

As for the lower spines, there are usually no separate groups among them, sometimes classifying them by the winglets they cover.

Feathers: the secrets of beauty

All the variety of colors, the amazing richness and elegance of the shades of plumage of birds is created by the pigments of the two groups and some peculiarities of the feather structure. The melanins accumulated in the horn cells in the form of clumps and grains give the feather shades of black, brown, reddish-brown and yellow. Lipochromes are also found there in the form of fat droplets or flakes and provide brightness of color: red (zooeritrin, phazianoeritrin), yellow (zooxanthin), blue (ptilopin) and other colors. The co-occurrence of several pigments in the same area of a feather greatly expands the spectrum of hues given here. In addition to imparting color, pigments, especially melanins, increase the mechanical strength of feathers.

Apparently, this explains the predominantly black or brown coloring of at least a part of the wing feathers in most birds, even having white as the main color of plumage (white stork, white goose, many gulls, etc.). An interesting exception here are species with "reverse" coloring, black with white feathers - black swan, two species of saddle-billed storks and horned raven of the rhinoceros family.

The white plumage coloration is due to the presence of transparent cavities filled with air in the feather horn cells, with the complete absence of pigments. If the cell walls are not transparent enough, the feather acquires a bluish or bluish tint. The metallic luster of feathers, characteristic of many birds, is formed due to the decomposition of light into a spectrum on the surface of the feather, where the outer keratinized cells are peculiar prisms.

All these above-mentioned ways are used to form the feather color; it only remains to add that it happens only during its development, and it is impossible to change the feather color during its life (except for the fact that, under the influence of natural factors, pigments are destroyed and, with time, feathers become a little faded).

It's time to scatter feathers...

Feathers don't last forever. With time they wear down, get broken, fade, they can be eaten by parasites (there are 2000 species of the feather mite superfamily and a whole group of insects - down eaters). Therefore, birds regularly change their feathery attire - molt. Every fan of wavy parrots and canaries can observe this phenomenon at home. To the horror of the owners, the feathers suddenly begin to fall out of the bird. But you should not panic and run to the vets and pharmacies. Wait a week or two and you will notice that your pet has some sticks sprouting between the remaining feathers. These are feather tubes. Subsequently, new feathers will emerge from them, bright and clean.

It should be remembered that in domestic birds molting can happen at any time of the year. For wild birds, the annual molt is usually confined to a certain season, only for some tropical species it can take place gradually throughout the year. The peculiarities of molting differ in different groups of birds, this topic is vast and deserves a separate discussion. Here it seems necessary to point out that in the process of molting there is an age-related and, for many species, a seasonal change of feather garments. Thus, one and the same bird can have completely different plumage during its life. Accordingly, there are several basic feathery outfits of birds.

Embryonic attire - is formed during embryogenesis and varies in degree of development in different cohorts, usually better developed in chicks with brood type of development. It may consist of embryonic down and embryonic feather (the latter can be found on the chicks of gooseflies, grousefishes, tinamus, as well as ostriches and the like). It is completely absent in swifts, woodpeckers, rickets, pelicaniformes.

Nesting attire. (juvenile, juvenile) - replaces the embryonic (if present), with some of it replacing embryonic down and feathers and some being formed in new feather papillae. The nesting attire may be worn by different species for different periods, from a few weeks to a year, and usually differs from the attire of an adult bird in color and plumage structure. In some species, differences in color are insignificant, and young are simply dressed more dully, without a characteristic sheen (crows, some tits, kingfishers, pigeons, many shepherds, etc.).

For other groups this difference is more noticeable. For example, in most representatives of the thrush family, which is quite diverse in coloration, the young are rather similar - pied due to bright light spots on the shaft and brown rims of the feathers. Gulls and pale terns have mottled, brownish-brownish chicks. White swans have brownish-gray chicks, white cranes have reddish-brown chicks, etc. - There are many examples.

Quite often the juvenile attire is mottled because of light ochre spots on the feathers. This type of coloration is considered to be evolutionarily more ancient for birds. In the presence of sexual dimorphism, it is similar to the coloration of females (ptarmigan, ducks, ruffians, and many passerines). It may simply be more faded - with a pronounced change of seasonal coloration it resembles the winter attire of adult birds (loons, grebes, many waders and guillemots, etc.). But even in those birds in which young birds have almost the same colouring as adults (warblers, some waders and tits and some other species), feathers of breeding attire always differ by structure from feathers of adult birds: first and second order beards on them are less often and more weakly adhered to each other, plumage makes an impression of looser and softer.

It is interesting that young guillemots and divers have two generations of juvenile plumage. The first generation of feathers replaces the embryonic down by the 20th day of life: these feathers are significantly shorter than those of the adult bird and more loose. In this attire, young guillemots and loons go to the sea and there, by 2 months of age, have already molted into the final version of the juvenile plumage, close to the plumage of adults. All other representatives of the guillemots have only one juvenile attire and put it on at the age of 1-1.5 months, at which time they leave the nest.

They often have The post-breeding outfitThe post-breeding molt is often singled out. It usually takes place in the first autumn of life before seasonal migrations; less often it is extended and ends during wintering. Usually this molt does not affect the flight feathers and sometimes the rudder feathers. Often, the post-breeding attire is practically indistinguishable from the adult in color and plumage structure, but some large birds (swans, gulls, raptors and others) do not acquire the final color until the 2nd , or even the 5th year of life. In such a case we speak about the first annual outfit, the second annual, etc.

Annual outfit (inter-breeding) is formed in adult birds after the post-mating (autumn) molt. Most often it begins after the end of nesting and departure of the last chicks and ends before the beginning of autumn migration, but there are numerous deviations from this scheme. Thus, in some species, usually of sufficiently large size, it begins simultaneously with the laying of eggs (hawks, finches, snowy owls, some raptors), others moult already on wintering grounds after the fall migration, or part of the plumage changes before migration and part after it, etc.

There is a widely known example of rhinoceros birds when the male molts "as it should be" and the female does it during the incubation period of the clutch, while the spouse walled her up in the hollow, leaving only a narrow opening for feeding.

The annual molt is worn until the next fall molt (unless the species has a nuptial molt, which will be discussed below). Autumn molt is almost always complete, with the exception of some large birds (herons, storks, eagles, etc.), which do not have time to change all their feathers during the molt and some of them change once every two years. In cranes, the molt of the fly feathers always occurs after one year.

В mating attire Birds usually molt before the breeding season in late winter-early spring, although there are exceptions (ducks begin to dress in mating feathers as early as August and finish in winter). The molt may be complete, but more often is partial, when all or only part of the fine contour feathers change, and the wing and rudder feathers remain. Moult occurs in both sexes, and the coloration of males may change, while females usually remain the same.

In some birds the change of color for the mating season is not due to molt, but to the wear and tear of the plumage. In spring, the male house sparrow has a striking black chin, throat, and upper part of the chest, although in autumn these areas were almost the same grayish-brown color as the surrounding plumage. In this case, the feather has a black midsection with light edgings in tone with the rest of the plumage, and since the feathers are tiled over each other, the black color is unnoticeable. Over the course of the year, the weakly pigmented (and thus less robust) edges of the feathers gradually wipe out, and by spring (i.e., by the beginning of the mating season) male house sparrows acquire their characteristic coloration. In the same way, the common starling, mottled in autumn, turns out to be a monochromatic black color with a metallic sheen in spring. "Revealed" by the breeding season is the red color on the males of the redstart, tap dance, linnet, etc.

A.V. TIKHOMIROVA

Peacock tattoo: meaning

Such a tattoo of a feather on a leg or other part of the body is often applied to themselves by women, because this bird has a beautiful coloring, which one wants to pay attention to. It has the following meaning:

- good luck;

- nobility;

- kindness;

- majesty;

- a sea of impressions.

Some cultures saw the tattoo as Satan's eye - in a colored circle, although the Greeks associated it with the sun and stars. Other peoples loved this tattooed image on the arm or belly as a symbol of vigilance, foresight and spiritual purity.

The peacock tattoo has many meanings, as well as locations: on the side, on the shoulder, on the neck, on the ear, and in all variants looked original and impressive (with photo sketches and inscriptions can be found below). Tattoo of the feather has many meanings, and almost every one of them is aimed at a positive direction.