Japanese Tattoo

The pedigree of the Japanese tattoo dates back almost 5,000 years. There are also some ancient Chinese texts, the first of which were dated around 297 AD. They talk about the Japanese tattoo tradition and mention that men of all ages have drawings on all parts of the body, including the face.

Dragons with snarling nostrils engulfed in flames, light pink sakura flowers floating in the wind, smirking hanni looks and geisha smiles... these are symbols of the Japanese Iredzumi tattoo. A tradition rooted in human history, Japanese tattoos are some of the most revered works of art in the tattoo community.

Traditionally Japanese tattoos began as a a means conveying social status, and also served as spiritual symbols that were often used as a kind of talisman to protect against harsh nature, and symbolized devotion, unlike modern religious tattoos.

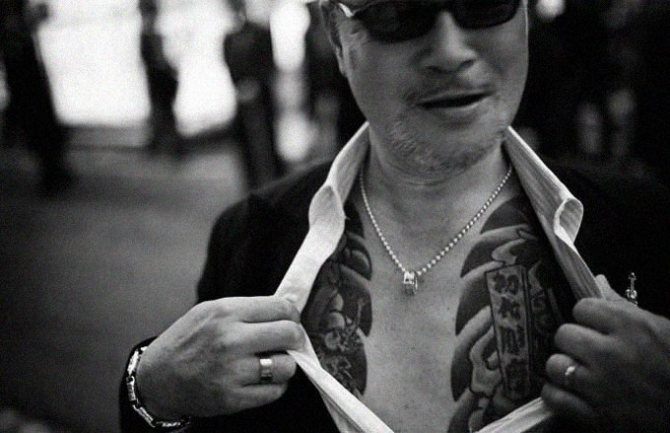

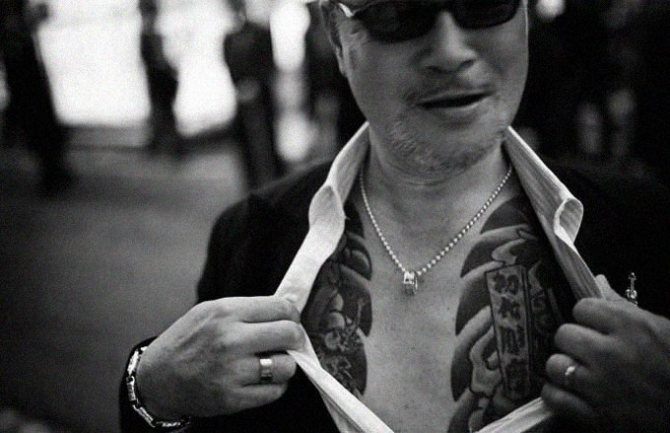

The prestigious attitude toward irezumi by international galleries over the past few years is in stark contrast to how tattoos are perceived at home.where many people see it as synonymous with thugs. People with even small tattoos may be banned from entering swimming pools and public baths .. Although tattoos have fallen out of fashion with the Yakuza in recent decades, this intolerance against ink in Japan is stronger than ever. In January, for example, a junior high school teacher in Osaka was fired for tattooing on his arm and ankle.

The gap in the perception of foreigners and Japanese in Iredzumi began over 150 years ago, when foreigners first saw Japanese tattoos. Since that time, however, Japanese tattoo artists have had a significant influence on their foreign counterparts- and sometimes vice versa. In some cases, it could be argued that international influence helped save Japanese tattooing from near extinction.

A Guide to Japanese Tattoo Culture

FURFUR continues to tell its readers about the current state of tattoo culture. This time we will talk about one of the most ancient traditions - the Japanese tattoo.

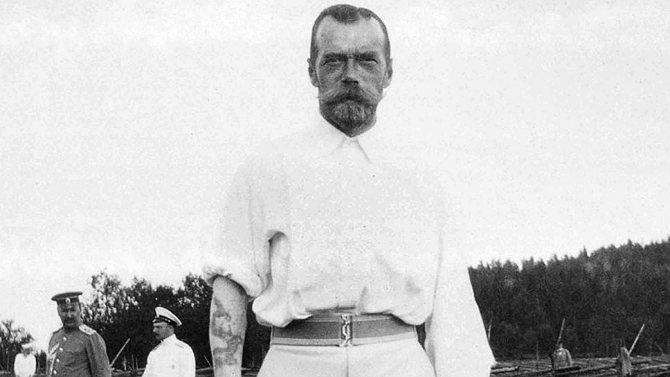

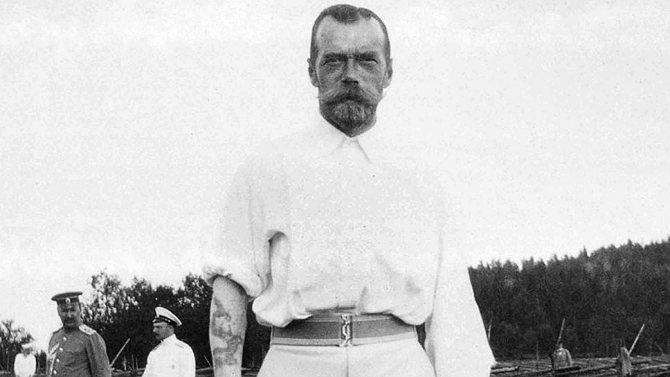

History The Japanese tradition in tattooing is considered one of the oldest and most influential. Its history goes back thousands of years, and its influence is evidenced by the fact that tattoos from Japanese masters were worn by the monarchs - the Danish King Frederick IX, the English Edward VII and, according to legend, even Nicholas II. Frederick IX King of Denmark | The tattooist has always been held in high esteem in Japan and considered a kind of artist. According to one version, at first tattooists worked together with engraving artists: one made a sketch on the body, while the other hammered it in. According to another, the tattoo artists were the same engraving artists who changed careers. In any case, the learning process was quite similar: for five years, the apprentice was apprenticed, scrubbing floors, mixing ink and, most importantly, learning classical drawing. |

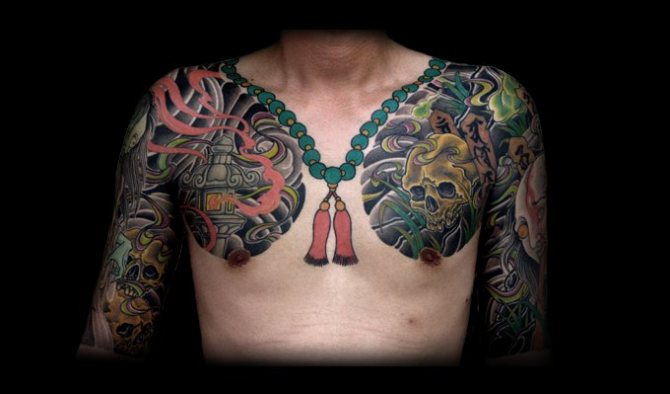

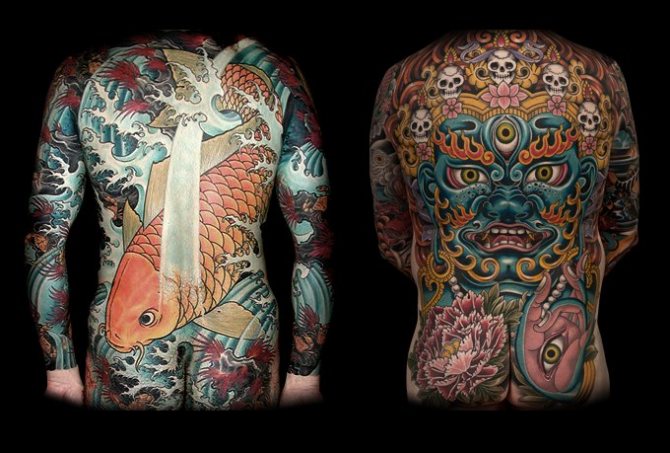

First of all, masters went to study in order to understand all elements of traditional design, their meanings and rules of their combination. In traditional Japanese tattooing, some elements are often placed together. For example, peonies are traditionally paired with the Japanese lion. All these nuances are the main difficulty of the Japanese tattoo: in order to draw a dragon, it is necessary to know clearly what kind of dragon it is, because this will determine not only its shape and color, but also its location on the back. The Japanese believe that just this aspect is inaccessible to foreigners - it is impossible to learn all the nuances and rules from books alone. And the most orthodox tattoo masters believe that even among Japanese tattooists today there is not a single tattooist who fully understands this art.

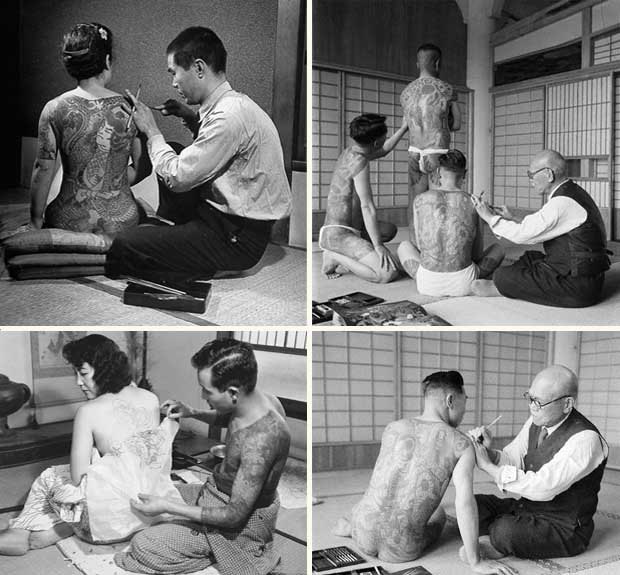

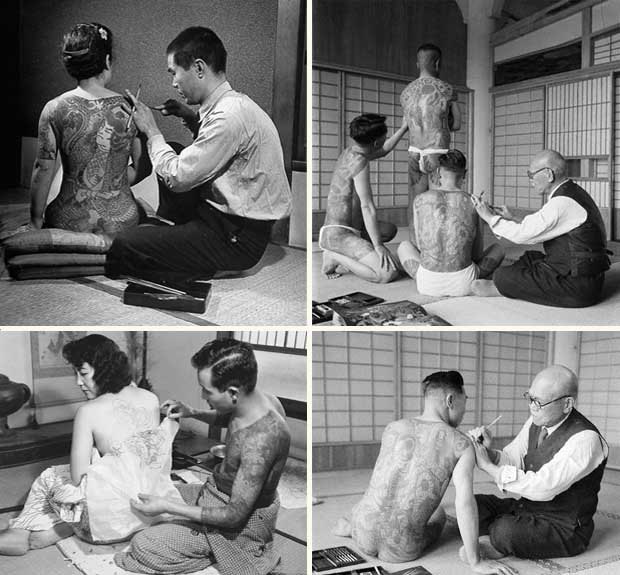

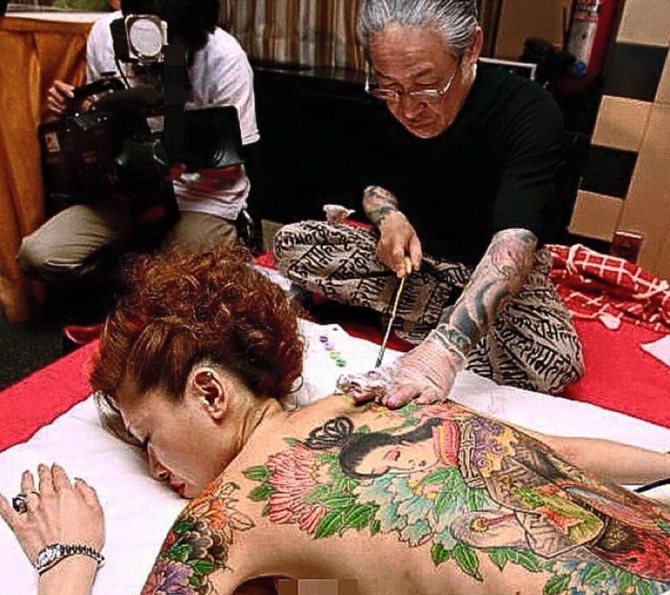

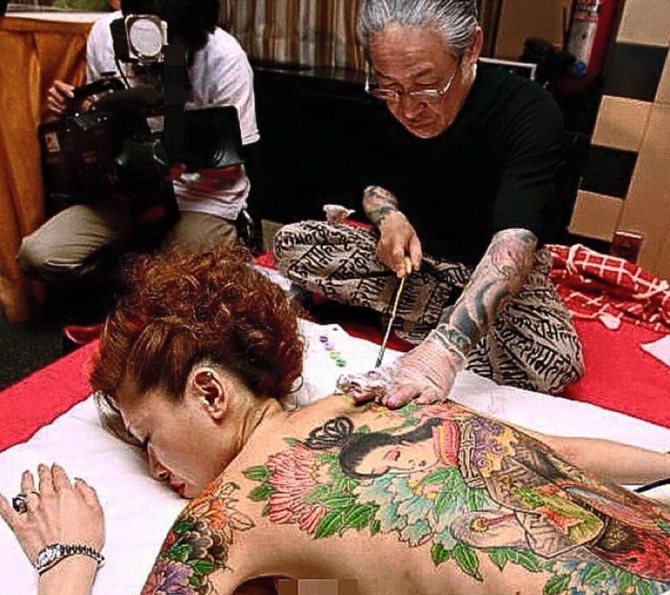

| Many old masters continue to use tebori bamboo sticks for tattooing. |

The traditions of Japanese tattooing have been preserved not only in the strict rules of drawing, but also in matters of technique. Many old masters continue to use special bamboo tebori sticks instead of a machine and claim that with a machine the result is quite different - the machine paints the skin more densely, and the sticks allow to reach another level of gradation of tones.

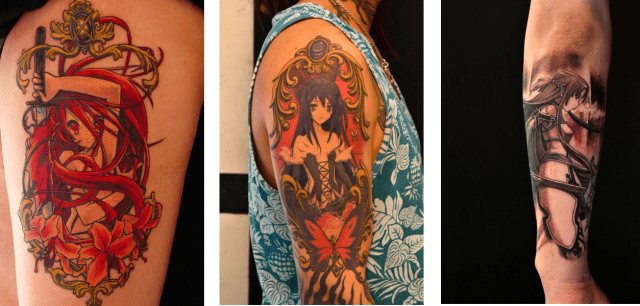

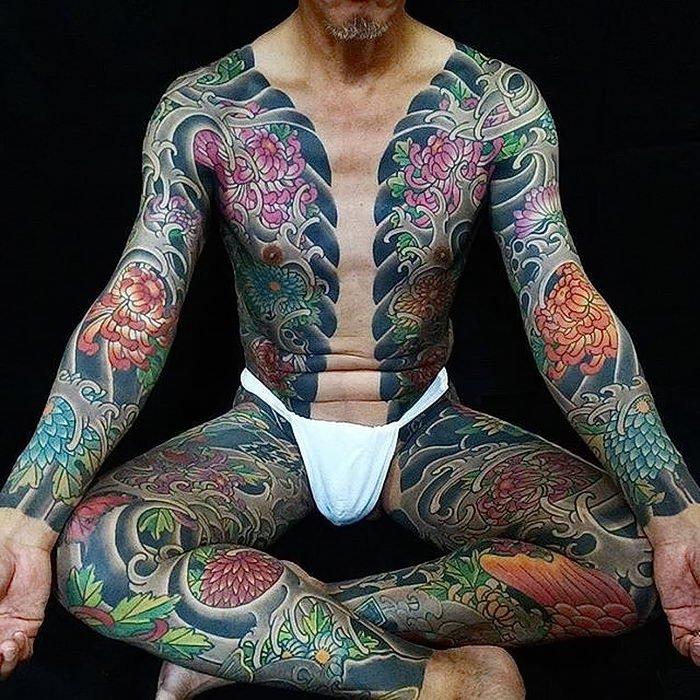

On the other hand, the typewriter saves a lot of time: traditional thebori tattoos are imposed manually, and the classic tattoo form, a "suit" that covers the whole body from shoulders to hips, takes a lot of time, sometimes around 200 hours. Although for some there is a specificity in this - the legendary master Horioshi III, for example, says that in the West people do tattoos too quickly and thoughtlessly, and continues to marvel that you can start and finish a tattoo in the same day.

One has to make allowance for the fact that the strict canon in Japanese tattooing is slowly falling away: the great masters are living out their century. The same Horioshi replaced bamboo sticks with metal spokes, and his admirers followed him, and since the 1990s, many have swapped spokes for a machine. Traditional training more and more often passes before training in the world's best tattoo parlors, and the postmodernism that came allows some liberties in the interpretation of classical plots.

In Europe and America are trying to make their own kind of oriental, which in search of personality brings to curiosities like a cubic geisha. Tattoo orientalist Oliver Peck says this about this phenomenon: "It used to be different: America, Europe and Japan had their own style. Now it's about the same everywhere, and more Japanese-style tattoos are done in America than in Japan itself."

What's happening now

A story about the Japanese tattoo would be incomplete without talking about how the tattoo is treated in Japan. The fact is that Japan is one of the few countries in which today the tattoo is still taboo. The reasons for this are generally understandable: for a long time the tattoo has been strongly associated with the Japanese mafia and, unfortunately, continues to be considered a mafia symbol, at least by the authorities.

Most gyms and swimming pools do not allow people even with tiny tattoos on the inside of the forearm, and for wider tattoos that are visible on the arms and legs, may be asked to leave even a bar or store. One recent sensational story was the campaign of Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto, who, under threat of dismissal, made all civil servants in the city report on their tattoos: where they are and what they depict.

It is hard to say whether the situation will change on its own over time. On the one hand, there are more and more people covered in tattoos every year, but on the other hand, tattooed Japanese continue to hide their tattoos. Tattoo artist John Mack believes that most Japanese think their neighbors don't have tattoos, but the truth is that they just don't show them.

John came to Japan to get a tattoo from Horiyoshi and liked to grab a drink at a local pub in the evening. When it came to tattoos, he would brag about his work from Horiyoshi - and every time he was asked to show the work. If the situation was right, John took off his shirt, and then sometimes a surprising thing happened: the other customers, both men and women, took off their shirts after him. And it turned out that they were all tattooed.

Masters of Japanese tattooing

Horioshi III.

|

It is rumored that Horiyoshi was a real gangster in the past. Horioshi III has been tattooing for over 40 years, and at one time learned according to all traditions from Master Horioshi II. It is no longer possible to make an appointment with him - he does not start new tattoos, only completes old ones.

At his 65 he remains one of the best experts on "costumes" and one of the central figures of the direction, which influenced the whole culture. At this point he is the author of 11 books and the founder of the Yokohama Harbor Tattoo Museum.

Shige

|

One of Japan's best young tattoo artists. Shige is known for his own style. Of course, he draws on the Japanese tradition, but gives it his own interpretation, mixing in Western influences - the work of Paul Rogers, Ed Hardy and Sailor Jerry.

For a long time Shige was self-taught in tattooing, until on one of his travels he met Philip Liew, from whom he decided to make himself a suit. Despite his blatant neo-traditionalism, Horioshi himself also praises Shige's work, even agreeing to write an introduction to his book and noting that Shige's work goes beyond traditional tattooing and has become art.

Miyazo

|

Another contemporary Japanese tattooist who is attentive to tradition, but also has his own handwriting and a very unusual style. And while Miyazo was classically trained by master Horitsune II of Osaka, he is quite progressive - for example, he started using a machine a decade ago.

Miyazo is one of the most influential Japanese tattoo artists of today, influencing, for example, Chris Brand and Drew Flors. Miyazo's importance is demonstrated by the fact that, along with Shige, he will represent Japan in the documentary series Gipsy Gentleman, about the world of tattoos.

Mike Rabendall

|

A New York tattoo artist who you have to sign up for a year in advance. Mike is famous for his respect for Japanese style and for doing tattoos for tattoo artists. And he once did a tattoo on a corpse (Mike did not elaborate on the details of this event). Mike started out in realism and orientalism, including Tibetan and Chinese, but came to traditional Japanese style. Mike is also a notorious moralizer: in all his interviews he advises tattooists who get involved with Oriental to read more books and to do everything by the rules.

Phillip Lew

|

A third-generation artist, Philip Liew loves the Japanese style and has a rare freedom of thought. Thus, he believes that using a particular style should not make a tattooist a conformist.

Philip has been tattooing since he was a child. His father was born in Japan and traveled with his wife (and later children) for almost 30 years around the world - India, Africa, Polynesia, America to learn national tattoo styles. Philip, on the other hand, is famous for his interpretation of costume Japanese tattooing - he took it to another level, and it's hard to imagine what neotraditionalism would be without him.

Expert's comment

Sergey Buslaev, master of Japanese tattooing: "The Japanese style is first of all the one that relies on the work made by the Japanese. Before such a tattoo is done, it should be researched. Most people don't think about it - there are, of course, those who come with a particular thing, but that's one person in 50. The rest ask for advice on what to do - then I give them translated Japanese books so they can figure out what's what. In Japan there is not only a dragon, a tiger and a carp, they have many different creatures, there are demons that are good and bad, samurai, masks, flowers.

As for my style, I started with realism and then I came to the Japanese style. The Oriental tattoo is very large, the full costume takes up the back and part of the legs, and yet it looks beautiful in one piece - I am interested in creating such drawings that become part of the person and complete it. Such tattoos take a lot of patience and time, they can take months and sometimes years.

| The year before last, a lot of people came in for carp. |

"I take all the symbolism from the books that the Japanese masters wrote. Why the dragon is this color, why it flies up and what it means, I try to make tattoos that match the meaning. Now it's very fashionable to make yourself a carp, to make yourself a dragon, but how, what to combine it with, where to do it best and how to think about the fact that in the future you want to continue the tattoo, and then neither here nor there, no one thinks about it.

In Oriental we have very cool masters, both in St. Petersburg and in Moscow. I like masters who understand that they draw and do not copy Shige's pictures. As a rule, self-respecting masters do not make copies, and I feel sorry for the people who will always walk around with this.

Irezumi's story

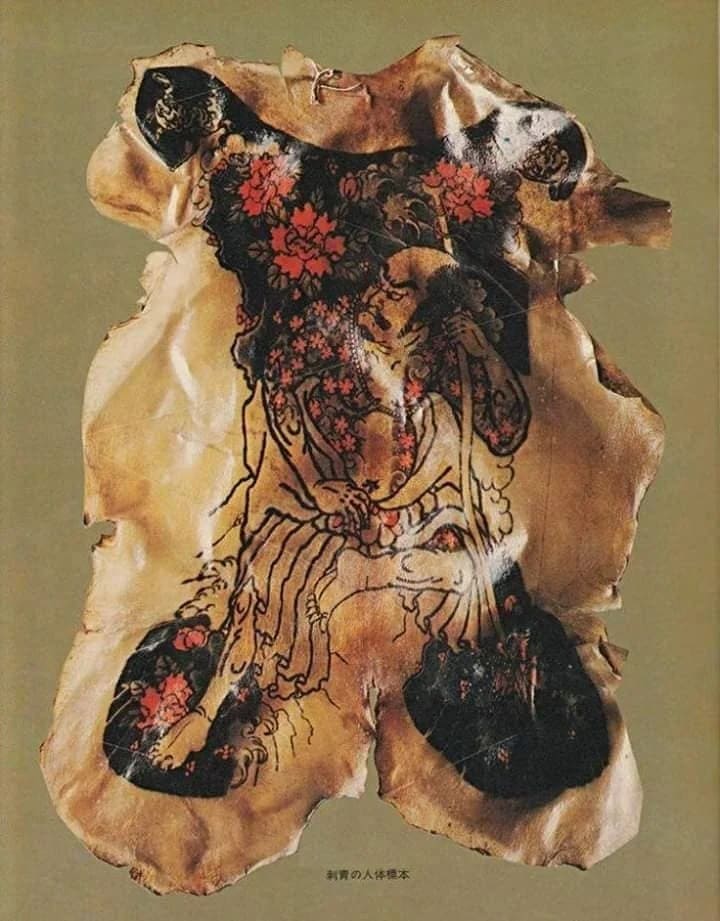

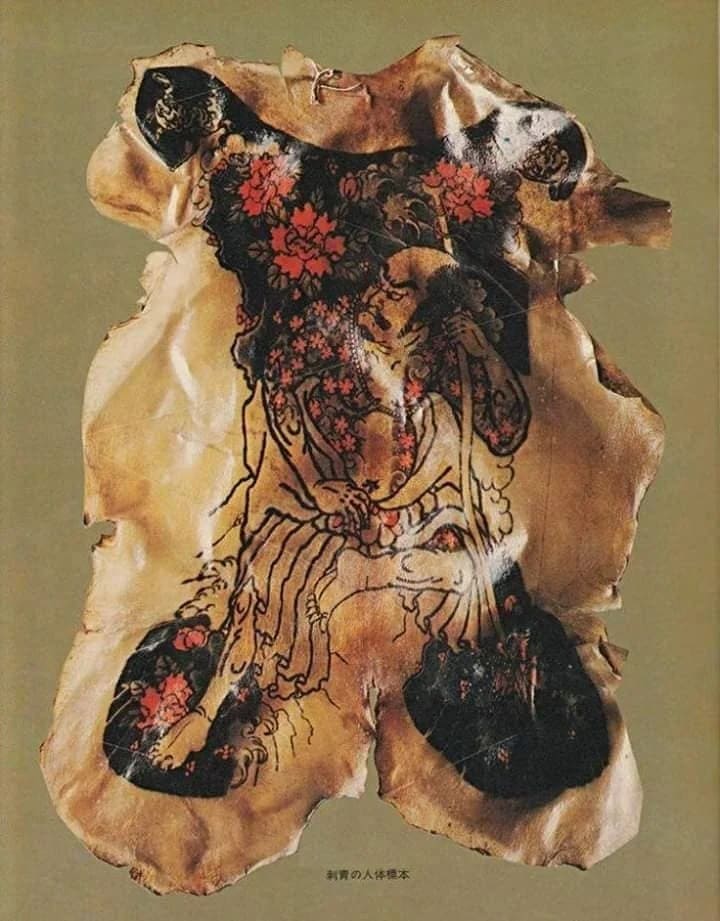

Creepy collection of Yakuza tattooed skin. 18+ Tokyo, photo.

During the Edo period (1603-1867) Japan was "drenched in ink." In Kyushu, miners wore dragon tattoos as talismansto protect themselves from the dangers of their work, and Ainu women in Hokkaido had tattoos on their faces to protect themselves from evil spirits. They were made by rubbing birch ash into small incisions. Tattoos were reserved for Ainu women and were created from a young age by the hands of priestesses. These tattoos were not only seen as a way to distinguish social status and adulthood, they were also deeply sacred and religious.

Okinawan women wore tattoos as a sign of beauty and maturity. Again, these Japanese tattoos were for women only, they were indigo in color and were done mostly on the arms and were applied to symbolize the beginning of marriage, femininity or social status. They were also thought to reflect evil and provide security in this life.

Edo - modern-day Tokyo - was the home of colorful full-body tattoos, especially popular among firemen, messengers and gamblers. Many of the drawings were based on wooden prints, ukiyo-e, and the two crafts were so intertwined that wood artists and tattoo artists adopted the common name hori (carving). - a tradition that continues among the Iredzumi masters today.

Ukiyo-e translates as "Images of the Soaring World," are woodcuts that still influence Japanese tattooing in many ways.

Depicting beautiful scenes of nature, the daily lives of courtesans and peasants, stories of war, ghosts, animals, and even erotic episodes. The style of ukiyo-e prints is very specific due to the fact that it is made from a block of wood, or several depending on the complexity of the design. Ukiyo-e prints were affordable because they could be mass produced. They were mainly intended for city dwellers who could not afford to spend money on paintings.

Surprisingly colorful, flattened perspectives, graceful illustrative lines, and a unique use of negative space all served as the basis not only for European artists such as Monet and Van Gogh, but also for craft movements such as Art Nouveau.

Distinctive features of Ainu culture.

The bans on irezumi during the Meiji period

However, tattooing was not widespread among samurai due to the growing influence of Confucian ideas, and Confucianism did not support self-mutilation. Many were also repelled by its use since 1720 as an additional punishment - some criminals were tattooed on the forehead or arm. The Shogun government repeatedly banned tattooing, but without much effect, and it reached a peak of popularity by the mid-19th century.

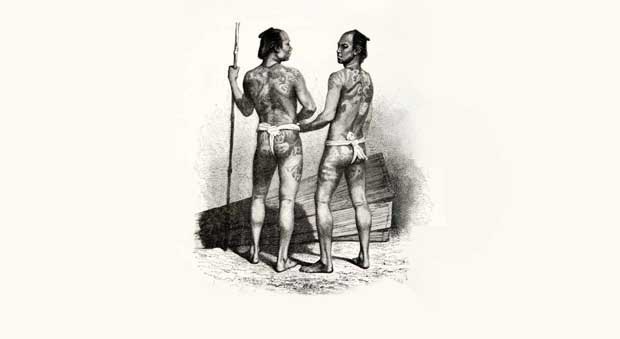

Then the Meiji government, opening the country to foreigners, set out to establish Japan as a civilized country on a par with Europe and America. The country's isolation ended, and all kinds of people - officials, tourists, and sailors - began to come to Japan from abroad. In their descriptions of their stay in Japan, they noted the custom of men and women bathing together, of men walking around the city wearing only the loincloths of men whose bodies were completely covered with tattoos.

Perhaps this is partly why from 1872 there were legal restrictions on tattoo artists and their clients. Since the beginning of the twentieth century it has become customary to always wear clothes, tattoos were hidden under them, and restrictions had a greater impact on tattoo artists than on clients. At the same time, the perception of the special "spiritual" beauty of the tattoo, manifested precisely by the fact that it is not visible, probably intensified.

Legislative restrictions applied to Okinawa and Ainu as well, and the tradition of women's tattoos came to naught. Some people tried to hide their tattoos, but they were caught by the police. The perception of irezumi as a barbaric relic spread, and they were often removed by surgery, or etched with hydrochloric acid, for example. The culture shock from the introduction of such restrictions still reverberates to this day, and people in those areas have all but forgotten these customs.

Yakuza and couriers.

Traditional Japanese tattooing, or iredzumi, has been intertwined with the yakuza since their inception. During the Edo period (1603-1868), the authorities tattooed criminals in a practice known as bokkei, making it difficult for them to re-enter society and find work. The yakuza tattoo culture became a mark of protest against this brand.

The meaning of yakuza tattoos is usually associated with images and symbolism of Japanese art, culture and religion. In particular, the full-body suit tattoo is a product of yakuza culture. In the past, in many yakuza clans it was mandatory for members to get tattoos. Nowadays, the practice is not as common. Conversely, more and more non-yakuza people in Japan are getting tattoos. Despite these changes, tattooing is considered a rite of passage for yakuza.

The open distribution of tattoos during the Edo period ceased in the mid-1850s with the arrival of international ships in Japan. The country had been closed to outsiders for more than 200 years, but now these unwanted visitors, including Commodore Matthew Perry and his infamous Black Ships, demanded that Japan open its doors to trade, a process that in other countries had led to to outright colonization. Desperate to avoid such a fate, the newly created Meiji government attempted to clothe the nation with the trappings of civilization: it encouraged people to wear Western clothing, banned samurai hairstyles and swords, and in 1872 banned tattoos.

Of course, many people continued to practice Japanese tattooing underground. For the most part, they belonged to the lower classes of society. Firemen, laborers and gang members, those who fought against state control and laws, all continued to be fond of tattoos. Ink was a symbol of bravery and courage, not only because of its illegality, but also because of the the intense pain of the long process.

For firefighters and others involved in dangerous feats, they also Were a protective element. Perhaps one of the main reasons criminals were so fascinated by tattoos was a Chinese novel called "An Account of the Feats and Adventures of 108 Noble Bandits. The long folio described how many of the characters had intricate tattoos illustrating legends and folkloric creatures.

The gang went gray: most in the yakuza are over 50 years old.

History of the style

The history of Japanese tattooing goes back thousands of years. It is one of the oldest types of body art. To this day skilled craftsmen from Japan keep the tradition of applying colored and b/w tattoos, preferring metal spokes and bamboo sticks to modern machines.

There is an opinion that the Japanese style was formed from the Polynesian images. First they were abstract compositions, then fish and animals.

The motifs varied, depending on the era. In the early Middle Ages, the use of body art was used to distinguish criminals and designate professions. There was a special sign of a traitor - a tattoo in the form of the Japanese character "dog". After the advent of the samurai, amulets and paintings demonstrating strength and courage became popular. During the so-called era of tranquility, tattoos became signs of love, and religious paintings and images of Buddha became popular.

During the dictatorship (17th century) tattoos were banned in Japan. And although people still made them and hid them under their clothes, the popularity of body art declined somewhat. A new flowering of this art form occurred, thanks to geishas, who made tattoos in the form of festive kimono.

Features of the style

The classic Japanese style is a tattoo, the meaning of which varies not only, depending on the symbols, but also their combinations.

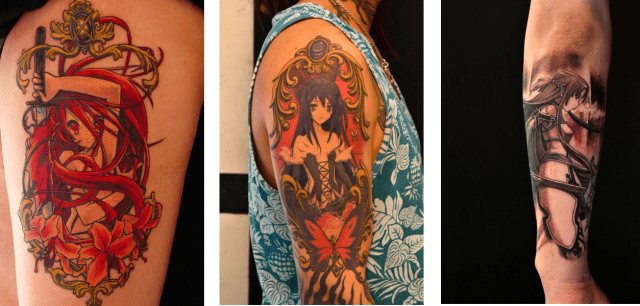

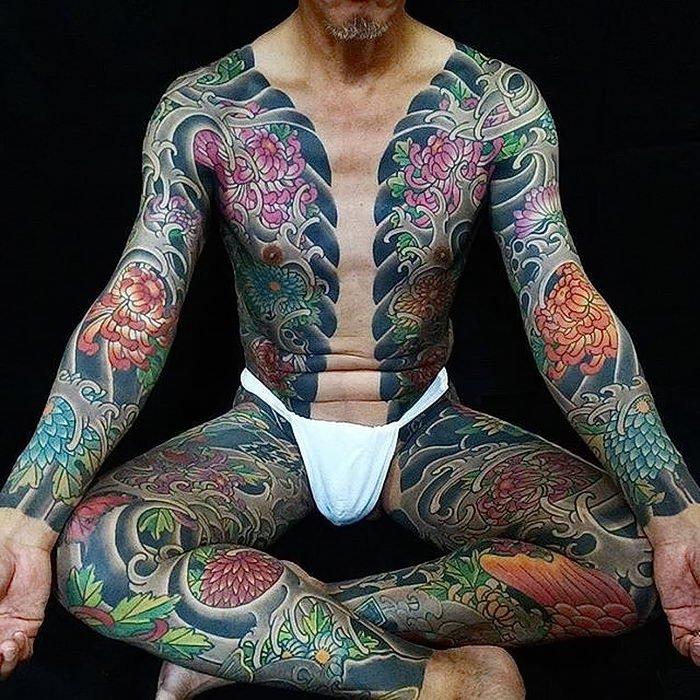

Photos of contemporary tattoos demonstrate that New Skool Japan is now popular in Japan. Clearly visible is the departure from the classic color combinations, drawings - complex and motley.

The most important distinguishing feature was and remains symbolism. Even a very small and at first glance inconspicuous detail can change the meaning of the whole picture.

Plots and meanings of Japanese tattoos

Sketches of Japanese tattoos in our studio are developed individually. Each image, hieroglyph or pattern has a sacred meaning, and you need to choose the composition with this in mind. Popular drawings:

- Sakura - the rapid flow of life.

- Tiger - strength and courage.

- Dragon - good luck, courage.

- Phoenix - loyalty, luck.

- Carp (Koi fish) swimming against the current - persistence, tenacity.

- Maple leaf - love.

- Hou-ou bird ("Hou-ou") - happiness, good luck, vitality.

- Sacred animal "Baku", which feeds on good dreams. Previously, his image meant protection from evil. Today in Japan, by dreaming on New Year's Eve, people predict good luck for the year, and going to bed, put under the pillow a drawing of a boat with wealth and the character for "Baku".

- The nine-tailed fox is a divine animal and its nine tails are a symbol of prosperity in the future.

- The animal Ki-rin is a sacred creature, promising prosperity and well-being.

- Ouryu - sacred fish, winged dragon, the highest form of dragon, which performs good deeds for the benefit of the emperor.

- Mukade - a poisonous centipede thought to be a ghost. It has a cruel essence, capable of biting anyone who touches it. These insects, according to the Japanese, can search for gold deposits.

- Jinki Eared Turtle - a divine symbol in many religions, which is worshiped and considered a messenger of God. Capable of predicting the future. Her image symbolizes protection.

- Rabbit Usagi because of unpredictable aggression and rapid reproduction is often considered a symbol of debauchery and obscenity of women. In alliance with the tiger demonstrates the greatness of nature.

- Taka bird, or hawk. Pride, strength, self-sufficiency.

- Uchide-no-Kozuchi is a sacred hammer whose movement depends on what the person holding it desires.

- The snake in Japan is a messenger of the god, praised by the people. White reptiles are the most sacred.

- A frog with three legs brings wealth and bodes well.

In Japan are also common hidden tattoos, called Kakushibori, which are usually done on the inside of the forearm. That is, they can only be seen by very close people. Their subjects can vary from humorous to erotic.

Very popular hieroglyphs, which are linked to the fashion of a beautiful legend. According to it, the Emperor Jimmu won the favor of the queen, thanks to his tattoos. And when he did, he tattooed her name along with the character for "life." After that, couples in love did the same, expressing love and devotion.

When choosing a Japanese-style tattoo sketch, especially a large-scale image across the back, "sleeve", etc., you need to know the meanings of colors as well. For example, white symbolizes death and sorrow in the East, and pink symbolizes happiness.

Who is suitable for the style?

In the photo in our "Gallery" you can see that men and women do tattoos in the Japanese style. This trend is relevant at any age and suits everyone who is interested in Eastern culture and puts sacred meaning in the body drawings.

The arrival of Europeans

But the move had unexpected consequences.

"The Meiji government believed that tattoos would be perceived by the West as a barbaric custom that should be hidden from Western eyes. But Western perceptions did not match Japanese predictions of culture, and to some extent at the highest level, tattoos were considered one of the most attractive aspects of Japanese culture," said Noboru Koyama, head of the Japanese department at Cambridge University Library The Japan Times.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, foreign sailors flooded Japanese ports, and as soon as they saw the Iredzumi worn byand Japanese couriers and rickshaws.many wanted to buy it as a souvenir.. To meet their demands--and in violation of its own prohibition--the Meiji government reluctantly allowed Japanese tattoo artists to open stores in areas reserved for foreigners, such as Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki .. Working behind doors closed to the Japanese, in the late 18th century these tattoo artists made, according to some accounts, three-quarters of all visitors to Japan.

An 1882 image from the Illustrated London News shows a foreigner getting a tattoo in Nagasaki.|

Many European aristocrats were among these foreigners impressed by the talents of Japanese tattoo artists. According to Koyama, who wrote a book in 2010 titled Nihon no Shisei for Eikoku Oshitsu (Japanese Tattoo and the British Royal Family). In 1869 Prince Alfred, one of Queen Victoria's sons, was the first of several members of the British royal family to get a tattoo in Japan. Twelve years later, Prince George - the future George V - had a blue-and-red dragon tattooed on his arm in Tokyo and then a second dragon in Kyoto.

Other European bluebloods inked in Japan in the late 19th century included those destined to play a crucial role in world history: the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, whose assassination in 1914 triggered World War I, and Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia, who was executed after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

Nicholas II

During his trip to the Orient in 1891, the future Russian emperor made a tattoo of a black dragon, which is considered a symbol of power, strength and wisdom. In the East, the dragon was associated with divine power, considered his protector and savior. In this picture, Nicholas II is proudly showing off his tattoo. It is known that the very procedure of applying this image took seven hours.

At the time, Japanese also continued to get tattoos in secret - most famously Matajiro Koizumi, the grandfather of former Prime Minister Junichiro, whose large iredzumi earned him the nickname "Minister of Tattoos. The practice remained illegal, however, and repression continued in 1880 and 1908, according to Koyama.

Resurgence and world renown

With the end of the Warring Provinces period (1467-1573) and the arrival of the long peace of the Edo period (1603-1868) tattooing returned. There are records mentioning how courtesans and their guests swore eternal love to each other by cutting off their little finger or drawing their partner's name on their bodies with a tattoo. Subsequently, the Yakuza began to use such ways of expressing their feelings.

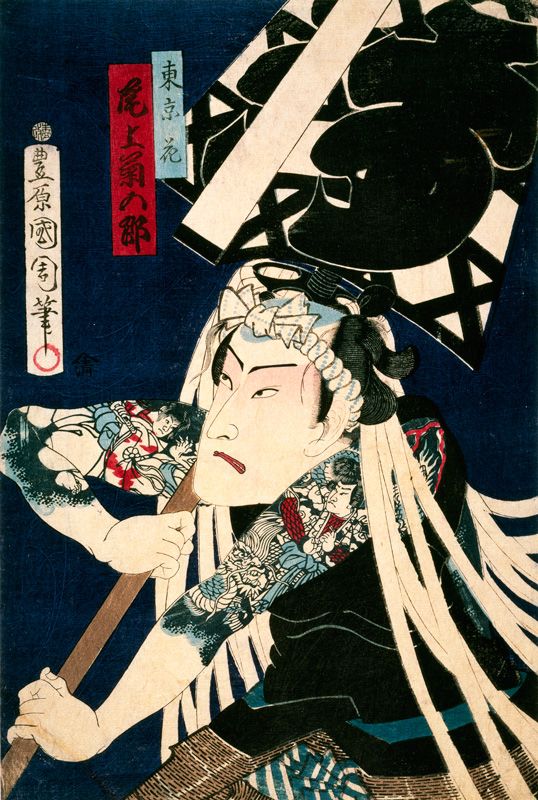

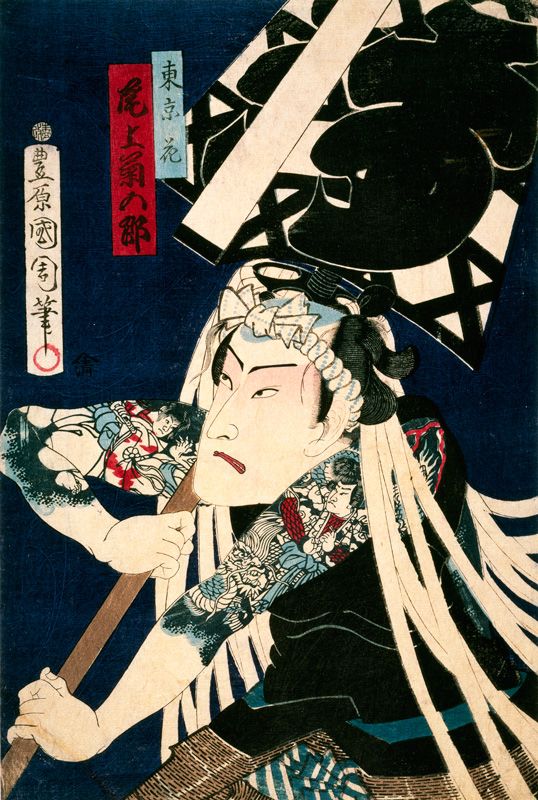

Toyohara Kunichika. Flowers of Tokyo - Onoe Kikugoro (© Aflo)

The now-famous Japanese tattooing technique (irezumi) and its tools reached their heyday during the Edo period. Iredzumi became popular with workers who often had to work in just fundoshi loincloths. It was painted on the body by tobi high-rise construction workers who were engaged in construction, holiday preparations, as well as guarding the streets and playing the role of firemen, hikyaku couriers, and workers in other professions. These were people for whom clothes got in the way while working, and without them they felt too naked, and so they decorated themselves with tattoos. Eventually the tattoo became perceived as so integral to the Tobi that sometimes organizations of city homeowners paid for tattoos for young builders who did not yet have them. The Tobies, who fought fires during the frequent fires, became a kind of symbol of Edonian chic, their tattoos considered pride and decoration of the neighborhoods where they lived.

The Tobi often wore tattoos with dragons. Dragons were believed to be able to cause rain, and it was one way to magically protect themselves. As the demand for tattoos grew, the art, which began with the depiction of written signs and simple drawings, gradually developed, the drawings became larger and more complex, leading to a special profession of tattoo artists who professionally adorned human skin.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Heroes of the popular novel "Riverwaters" - Rory Hakuyo Zhang Shun (© Aflo)

Popular culture developed a romantic image of the tattooed yakuza as someone who helps the weak and overpowers the strong, and they were portrayed in ukiyo-e prints. They were admired, and in the first half of the 19th century, the artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi, who illustrated the Chinese novel Shui hu zhuan (River Waters), which describes the deeds of "noble thieves," depicted them completely covered in tattoos, and the book was a great success. Subsequently, prints by Utagawa Kunisada and other artists depicting Kabuki actors with irezumi became very fashionable. This had its effect on the actual Kabuki theater as well, and the main roles in plays such as The Five Thieves (Shiranami gonin otoko, 1862) were performed by actors dressed in tattooed clothing. This stimulus from ukiyo-e helped irezumi to become more widespread, and the entire body was tattooed.

Utagawa Kunisada. The Hamamatsuya scene from the Kabuki play The Five Thieves (© Aflo)

World War II.

During World War II, these bans were again tightened in response to the desire of young Japanese to priedzumi in an effort to evade conscription. Imperial authorities perceived people with tattoos as non-conformists and potential sources of trouble in the armed forces.

Ironically, after Japan's surrender in 1945, the Allied occupation opened a new chapter in Iredzumi history. Many Yanks were already wearing plain American tattoos, which Japanese tattoo artists disdainfully called "sushi" because of their simplicity and poor placement on the body-but when these Americans saw large Japanese tattoos, they realized that American tattoo artists were simply scratching the surface of what could be achieved with a needle and ink.

Yakuza Skin, Museum In Tokyo.

One of the American servicemen most impressed by the Japanese tattoo was a confidant of General Douglas MacArthur, head of the Allied occupation forces. After meeting the famed master drawer Horiyoshi II, the advisor became so convinced that Iredzumi was an art worthy of U.S. intervention that he convinced his boss to legalize the tattoo. In 1948 the ban was lifted, and for the first time in more than 70 years, Japanese yredzumi artists were allowed to practice their craft without fear of persecution.

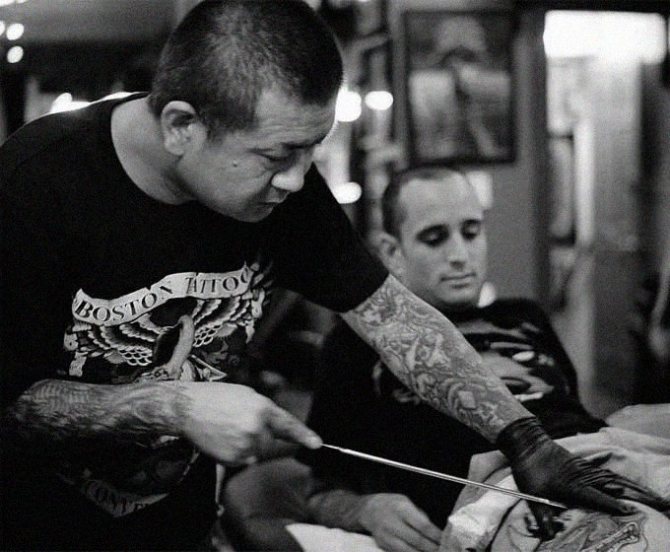

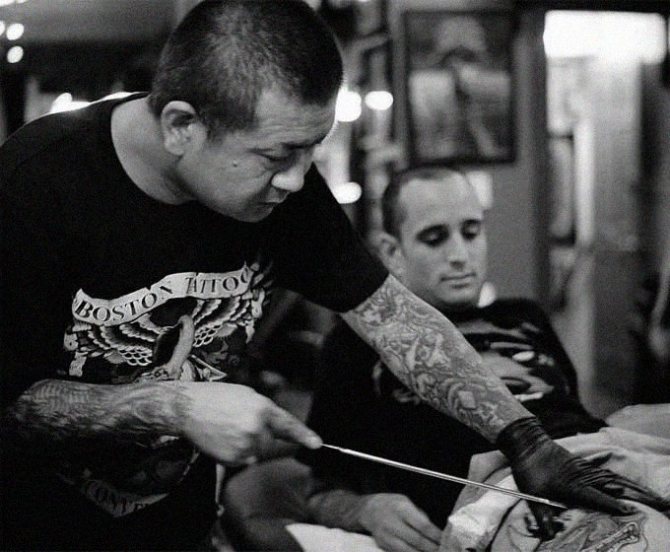

In the years that followed, many exchanges arose between Japanese and American tattoo artists, which inspired and developed tattooing on both sides of the Pacific.

A fight broke out in Kabukicho between 50 yakuza.

One of the most famous of these was initiated by Norman Keith Collins, better known by his trade name Sailor Jerry. A tattoo artist by day and ultra-conservative DJ by night, Jerry became pen pals with two of Japan's most talented tattoo artists, the aforementioned Horiyoshi II and Horihide. After exchanging American pigment, a commodity that was hard to come by in postwar Japan, for Japanese samples, Jerry became obsessed with Iredzumi and tried to master it for himself.

In the 2008 documentary "Hori Smoku, Sailor Jerry." Don Ed Hardy, perhaps the most famous living tattoo artist in the United States and friend of Jerry's., explained that his associate's fascination with Iredzumi was due in part desire to avenge the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. "We're going to learn it, and we're going to win their own game," Hardy recalled of Jerry's motivation.

Jerry Hardy

Thanks to Jerry Hardy's introduction, he visited Japan himself in 1973 to study the Iredzumi in person. Now that his name is a brand adorning everything from T-shirts to hair dryers to disposable lighters, it's easy to forget Hardy's pioneering role during that period. In his 2013 autobiography, Wear Your Dreams: My Life in Tattoos, Hardy writes, "No white guy ever got tattoos there. I worked behind a screen of shoji."

Hardy, however, didn't like what he saw on his first trip. Part of the problem was the timing: Hardy arrived in Japan in the 1970s, at the height of the popularity of tattoos among the country's criminal class. He quickly became disillusioned with both his clientele (all gangsters and sailors) and his clientele's approach to Iredzumi, which was often just as formulaic, as the Cold War tattoos of hearts and anchors that prompted Hardy to flee the United States in the first place. For example, when one young bandit asked Sensei Hardy for a tattoo of a kappa, a water demon, he refused on the grounds that it was not an appropriate object.

A kappa, is a small mythical creature in a green, puffy pelt, with a small hole in its head, shaped something like a chalice. According to popular belief, the Chalice is a symbol of life force. And as long as the waterman has even a drop of water in his cup, he is invincible.

Although Japan disappointed Hardy, his 1973 trip reinforced his passion for large-scale Iredzumi, and upon his return to the States, he opened a studio devoted exclusively to custom tattoos combining Western and Japanese influences. Over the next few years, he tattooed countless people, each of whom became a walking advertisement for irezumi in the United States.

Horiyoshi III.

Tattooing is still illegal in Japan for those who work without a medical license. In 2015, Taiki Masuda, a tattoo artist from Osaka, was raided by police at his studio and fined $3,000 for tattooing without a medical license. Still fighting the charges against him, his case remained open in 2021.

Horiyoshi III (Hiroyoshi) is one of Japan's greatest tattoo artists.

Because of the illegality of Japanese tattooing, many artists practicing in Japan have gone underground, and their studios are often hard to find. Nevertheless, tattooing fortunately still continues, not only by traditional Iredzumi masters such as Horiyoshi III, Horitomo, Horimasa, Horikashi and Horitada, but also by non-Japanese tattoo artists who practice in Japan and other parts of the globe.

According to Horiyoshi III - perhaps the most famous currently licensed Japanese tattooist - a chance encounter with Hardy in 1985 irrevocably changed him.

"Before I met him, I was a slacker. But when I saw how much Hardy knew about Japanese art culture and history, I felt so guilty that I began to study hard. I went to the library and studied everything I could for 20 years. Without Hardy, I wouldn't be who I am today," Horiyoshi III told the Japan Times in a recent interview.

Today, the "strange fusion of East and West" of modern Iredzumi is most evident at the Yokohama Tattoo Museum, founded by Horiyoshi III in 2000. Its two crowded floors offer visitors a crash course in tattoo history, from Meiji-era photographs to anti-tattoo rulings, and a display of ukiyo-e prints that inspired early artists. Along with these items are sheets of classic American flash designs and vintage American tattoo machines. Many of these artifacts are incredibly rare, but the museum is decrepit and, by its founder's admission operates at a loss.. Its dusty shelves and lack of visitors more than anywhere else encapsulate a lack of respect for the Iredzumi in the country where he was born.

The owner of another museum, Kimura of JANM, located almost 9,000 km., believes that the Perseverance exhibition will help bridge the gap between Japanese and international attitudes toward tattoos.

It is not only the preservation of artistic traditions, but also the reinterpretation and preservation of the relevance of symbols and mythologies of traditional Japanese literature and art. Iredzumi continues to live on ... visual narratives that would be almost lost to modern generations. It is something the Japanese and Nikkei (their overseas descendants) should be proud of and embrace.

Kimura hopes that one day the show will even go on tour in Japan.

Regardless of the depth of meaning, the high quality of artistic craftsmanship, and the important cultural and historical aspects of the Japanese tattoo, its protest significance should be noted. With modern ties to gang members, yakuza and criminal activity, tattooing is still done for reasons directed against government officials and mainstream society.

Reality

In 2012, The Economist published an article about Iredzumi that mentioned that Toru Hashimoto, then mayor of Osaka stated, "on a mission to force his government's employees to admit to any tattoos in obvious places. If they have them, they must remove them - or find work elsewhere." This view is shared by much of the professional world in Japan, and indeed by much of society.

Japanese tattooing is an incredibly important cultural art form that must be preserved, maintained and cultivated with understanding and respect. Its beauty lies in the enormous historical and symbolic aspects that make it a source of inspiration for artists. Bright kimonos, water lilies of the floating world, Buddhist deities and irresistible, dynamic dragons from ancient folklore - Iredzumi is one of the foundations of modern tattooing that deserves full reverence and admiration.

Views: 1,662

Share this link:

- Tweet

- Share entries on Tumblr

- Telegram

- More

- via email